|

Member-only story

An Unexpected Ally In Dementia Prevention: Shingles Vaccination

The strongest causal evidence yet from a 'natural experiment' study.

Idid a joint BSc(Hons) degree in biology-psychology and then an MSc in life sciences (major in neuroscience). I believe I went through over 50 textbooks throughout my student years. (Yes, I was a study freak.) But nowhere in the textbooks did I ever come across the theory that infections could 'seed' or promote the development of dementia.

Dementia refers to disorders involving memory loss, of which the most common type is Alzheimer's disease (AD). Established textbook knowledge informs us that AD is caused by a build-up of amyloid plaques in the brain. But what causes this build-up exactly remains unknown.

Convincing research in the last two decades has pinpointed infections, notably herpesviruses, as the likely cause, which I've written about before in Medium here. If infections are a risk factor for dementia, then vaccines targeting those infections should be a protective factor.

Association between vaccination and dementia

Indeed, numerous studies have found an association between vaccination and reduced dementia risk. Here are a few notable ones:

- Wiemken et al. (2021): Both herpes zoster and Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis) vaccinations lowered the risk of dementia by 30–50% compared to no vaccination or just one vaccination in a cohort of over 200,000 participants in the U.S.

- Veronese et al. (2022): Influenza vaccination reduced dementia risk by 30% over the span of 9 years in a meta-analysis of 5 studies involving nearly 300,000 older adults from Taiwan, Canada, and the U.S.

- Wu et al. (2022): General vaccination decreased dementia risk by 35% in a meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 1.86 million participants, mostly from the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and Taiwan. In subgroup analyses, all types of vaccines studied reduced dementia risk, which included rabies (57% ↓), Tdap (31% ↓), herpes zoster (31% ↓), influenza (26% ↓), hepatitis A (22% ↓), typhoid (20% ↓), and hepatitis B (18% ↓) vaccines.

Although these studies control for important variables (e.g., age, sex, medical conditions, and education), unmeasured confounding is bound to exist. These studies are observational by design, which can't control for every possible variable that may have influenced the results.

For instance, the healthy vaccinee bias is a prominent confounding variable plaguing vaccine observational studies. This bias denotes that vaccinated people tend to be more health-conscious and healthier overall. And those who are ill may delay vaccination until they get better, which may result in more favorable outcomes in the vaccinated group.

To overcome the limitation of unmeasured confounding, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed. Because RCTs randomly allocate individuals into the vaccine or placebo group, it nullifies the effect of confounding and allows us to determine cause and effect.

For instance, randomization prevents individuals from choosing to get the vaccine or not based on their health and economic situation. But to perform RCTs on vaccines with proven benefits is unethical as it entails withholding life-saving vaccines from those who need them. RCTs are only ethical when we don't know if the vaccine works or not.

Does that mean RCTs are the only way to confirm if vaccination truly prevents or reduces the risk of dementia? We thought so.

But a unique 'natural experiment' study, recently released on the medRxiv preprint server, proved us wrong. The study, "Causal evidence that herpes zoster vaccination prevents a proportion of dementia cases," was conducted by Eyting et al. from Stanford University, U.S., Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany, and University of Vienna, Austria.

The strongest evidence yet

Eyting et al. cleverly leveraged the fact that starting from 1 September 2013, the eligibility for the herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) for preventing shingles depends on the individual's date of birth in Wales, U.K.

Individuals born before 2 September 1933 were ineligible, while those born on or after 2 September 1933 were eligible for the vaccine, as Zostavax's efficacy is limited to those younger than 80 (2013–1933 = 80 years).

After excluding those with a history of dementia, 282,541 participants were available for the study. These participants were followed from 2013 to 2021 — in such a manner that the vaccine-eligible and ineligible groups were compared at similar ages — to track new diagnoses of dementia.

"[Apart from] the probability of ever receiving the herpes zoster vaccine, there is no plausible reason why those born just one week prior to 2 September 1933 should differ systematically from those born one week later," Eyting et al. said. "This unique natural randomization, thus, allows for robust causal, rather than correlational, effect estimation."

Their results were as follows:

- Firstly, they replicated previous RCT's finding that the vaccine-eligible group has reduced the incidence of new shingles cases.

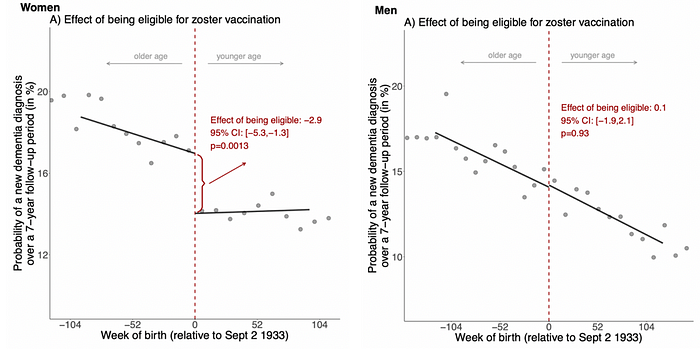

- Second, using the same analyses but a different endpoint, i.e., new dementia, they found that the vaccine-eligible group had a 20% reduced occurrence of dementia relative to the ineligible group over a 7-year period, translating to a 1.3% absolute* reduction (Figure 1).

- Third, they showed that the vaccine-eligible group (i) only had reduced dementia occurrence and not other diseases (e.g., cancer and diabetes), and (ii) did not seek any more vaccines or healthcare utilization than the vaccine-ineligible group — thus, ruling out the effect of confounders. (If there was healthy vaccinee bias, then risk reduction in other diseases and more vaccine uptake would also be seen.)

- Fourth, they showed that no other interventions, such as health insurance eligibility, adopted the same cut-off date of birth as herpes zoster vaccination (2 September 1933) for eligibility in Wales.

- Fifth, they found that if the 7-year follow-up was shifted 7 years earlier when the herpes zoster vaccine was not available and used the same analysis, no changes in dementia occurrence were noted.

*To understand relative vs. absolute risk, consider the example of a drug reducing pain from 10% to 5%. The relative risk reduction is 50% (5/10*100 = 50) and the absolute risk reduction is 5% (10–5 = 5).

"By taking advantage of the fact that the unique way in which the zoster vaccine was rolled out in Wales constitutes a natural experiment, and meticulously ruling out each possible remaining source of bias, our study provides causal rather than associational evidence," Eyting et al. wrote.

"Our rigorous causal approach allows for the conclusion that herpes zoster vaccination is very likely an effective means of preventing or delaying the onset of dementia," Eyting et al. continued.

That said, no study is flawless, and Eyting et al. and other experts have pointed out a few caveats of the natural experiment study:

- Intriguingly, the protective effect of herpes zoster vaccination was only evident in females, not males (Figure 1). Reasons for this could be that (i) herpes zoster virus plays a greater role in dementia in females, (ii) females respond better to the vaccine, or (iii) the known fact that shingles and dementia affect females more often than males.

- Follow-up was a maximum of 8 years; however, dementia evolves over decades, so the herpes zoster vaccine may simply delay the occurrence of dementia, not necessarily thwart it completely.

- RCTs are still needed to confirm (i) the frequency and timing of herpes zoster vaccination that could provide the maximal benefits in reducing dementia occurrence, and (ii) whether the newer herpes zoster vaccine, Shingrix, has the same protective effects.

Herpes zoster virus and dementia

Herpes zoster virus first causes chickenpox. Then, it stays dormant in neurons and may reactivate in later life to cause shingles (painful rash) under conditions of immunosuppression or stress.

Among the 8 types of herpesviruses known to infect humans, we only have an approved vaccine for herpes zoster. Remember, herpesviruses are the prime suspect in the infectious etiology of dementia.

Herpesviruses, mainly herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), have been found to:

- Cause dementia in animals and lab-cultured human mini-brains.

- Increase the risk of dementia in humans.

- Be present and co-localize with amyloid plaques in brain autopsies of patients who died from dementia.

Although the evidence mainly identified HSV-1's contribution to dementia, herpes zoster virus also plays a role. A recent study found that herpes zoster infection alone did not trigger amyloid aggregation in neurons, while HSV-1 infection did. But in the presence of HSV-1 latency, herpes zoster infection caused HSV-1 reactivation, triggering more amyloid aggregation than HSV-1 infection alone. And about 70% of the world population harbors latent or dormant HSV-1 and herpes zoster infections.

The natural experiment study of Eyting et al. further adds weight to the importance of the herpes zoster virus — among other variables like lifestyle choices, pre-existing medical conditions, and genetics — in dementia risk. It's a well-designed and innovative study bearing similar implications as an RCT, providing the strongest causal evidence yet that herpes zoster vaccination protects against the development of dementia.

If you have made it this far, thank you. Subscribe to my Medium email list here. If you want to become a member to get unlimited access to Medium, you can use my referral link, and I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. You can also tip me here if you are feeling generous today, and I will appreciate any financial support I can get.

One of those "other factors" may be how well you take care of your mouth:It may be that high-quality daily flossing your teeth is also a major factor in preventing Alzheimer's.

No comments:

Post a Comment