This newsletter will always be free, but paid subscribers help make this work possible. Please consider a contribution if you can! Coming Soon: Don't think of book club!A public reading and study of "The ALL NEW Don't Think of an Elephant"

What are Republicans for?" asked President Joe Biden during his recent one-year press conference. "What are they for?" I spent most of my career trying to answer this question. Several of my books – including "Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think" and "The ALL NEW Don't Think of An Elephant!: Know Your Values and Frame The Debate" – deal with the question in clear and direct terms. Yet Democratic leaders appear to remain in the dark about the fact that most Republicans have a completely different worldview, one that is increasingly incompatible with the outdated notion of bipartisanship or the crucial idea of democracy. Today's Republican Party has no interest in compromise or collaboration. The GOP has bloomed into a full-fledged enemy of the American idea of government and become an aspiring authoritarian organization. Fearing the power of the majority vote, Republicans are working feverishly to dismantle the machinery of democracy and make it harder for Americans to exercise the basic right to vote. The GOP has replaced loyalty to the country with the worship of one man, Donald Trump, who considers himself more important than the nation. Trump and his party demand that the Republican faithful be willing to sacrifice their lives on the altar of lies (as we have seen with the attempted insurrection of January 6 and the anti-scientific campaign against COVID vaccines). This is all happening in public view, with full-throated participation from all but a handful of Republican leaders. In fact, one of the most terrifying aspects of today's Republican Party is the utter shamelessness with which it peddles lies, conspiracies and anti-democratic ideas (with help from the Fox channel and other propaganda operations). This is not a political party that is planning for a future in which it must reach "across the aisle" to build coalitions and find agreement with the opposition. Today's GOP seeks to destroy democracy. It wants a future in which voters, laws and the Constitution no longer matter. If these Republicans get their way, the only thing that will matter is the opinion of an authoritarian leader who will dictate the definitions of right and wrong, legal and illegal, true and false. This authoritarian outlook has already devoured the GOP. The only question now is whether it can conquer the rest of the country. None of this should come as a surprise to anyone familiar with how Republicans think, which is based on a specific moral framework that has been fully exposed in the Trump era. I have written about this moral framework in seven books and have tried to get Democratic leaders and progressives to pay attention to the logic behind strict conservative thought. Unfortunately, the hour is getting late, American authoritarianism is on the march and we are living the consequences. What are Republicans for? A world in which voters wield no power over political outcomes. A world in which the law is whatever the strongman leader says it is. A world in which lies become truth and truth becomes lies. A world in which the rights and freedoms of the majority are systematically stripped away to empower the tyranny of the few. A world in which the white, the male, the Christian, the rich, the straight and the old wield maximal power over everyone else. This explains many things about today's Republican Party – including the reason why GOP leaders have no interest in collaborating with President Biden or helping him — or any Democratic leader — to succeed. So, what can we do about it? The first step is to understand what we're dealing with so that we can understand the dynamics at play. Unless we understand the frames behind conservative political thought, we will be unable to counteract their strategies and tactics. And the only way to understand them is through study and discussion. During February and March, we will be hosting a virtual but interactive book club to review and discuss the ideas set out in "The ALL NEW Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate." The book has five parts and an introduction, and we will go through it part-by-part over the span of a few weeks. I will answer questions and provide commentary to help readers understand the book in the greatest depth possible. Answers will be provided via the FrameLab podcast and this newsletter. The book is available to buy in many books stores and through outlets like Bookshop, East Bay Booksellers, Powell's and Amazon. Or you can support your local bookstore or public library, which may even offer a free e-book or audiobook for use. We will plan to start the discussion and Q&A sometime in mid-February, so this gives everyone a chance to acquire a copy of the book and read the intro and Part One. Are you in? Please let us know in the comments section, subscribe to the FrameLab newsletter and be on the lookout for further instructions in the coming weeks. (And a big Thank You to the hundreds of readers who have already expressed an interest in participating!) You're a free subscriber to FrameLab. For the full experience, become a paid subscriber. |

Sunday, January 30, 2022

Fw: Coming Soon: Don't think of book club!

Saturday, January 29, 2022

ANS -- "A DAY IN THE LIFE OF JOE REPUBLICAN" plus

"A DAY IN THE LIFE OF JOE REPUBLICAN"

Joe gets up at 6 a.m. and fills his coffeepot with water to prepare his morning coffee. The water is clean and good because some tree-hugging liberal fought for minimum water-quality standards. With his first swallow of water, he takes his daily medication. His medications are safe to take because some stupid commie liberal fought to ensure their safety and that they work as advertised.

All but $10 of his medications are paid for by his employer's medical plan because some liberal union workers fought their employers for paid medical insurance - now Joe gets it too.

He prepares his morning breakfast, bacon and eggs. Joe's bacon is safe to eat because some girly-man liberal fought for laws to regulate the meat packing industry.

In the morning shower, Joe reaches for his shampoo. His bottle is properly labeled with each ingredient and its amount in the total contents because some crybaby liberal fought for his right to know what he was putting on his body and how much it contained.

Joe dresses, walks outside and takes a deep breath. The air he breathes is clean because some environmentalist wacko liberal fought for the laws to stop industries from polluting our air.

He walks on the government-provided sidewalk to subway station for his government-subsidized ride to work. It saves him considerable money in parking and transportation fees because some fancy-pants liberal fought for affordable public transportation, which gives everyone the opportunity to be a contributor.

Joe begins his work day. He has a good job with excellent pay, medical benefits, retirement, paid holidays and vacation because some lazy liberal union members fought and died for these working standards. Joe's employer pays these standards because Joe's employer doesn't want his employees to call the union.

If Joe is hurt on the job or becomes unemployed, he'll get a worker compensation or unemployment check because some stupid liberal didn't think he should lose his home because of his temporary misfortune.

It is noontime and Joe needs to make a bank deposit so he can pay some bills. Joe's deposit is federally insured by the FSLIC because some godless liberal wanted to protect Joe's money from unscrupulous bankers who ruined the banking system before the Great Depression.

Joe has to pay his Fannie Mae-underwritten mortgage and his below-market federal student loan because some elitist liberal decided that Joe and the government would be better off if he was educated and earned more money over his lifetime. Joe also forgets that his in addition to his federally subsidized student loans, he attended a state funded university.

Joe is home from work. He plans to visit his father this evening at his farm home in the country. He gets in his car for the drive. His car is among the safest in the world because some America-hating liberal fought for car safety standards to go along with the tax-payer funded roads.

He arrives at his boyhood home. His was the third generation to live in the house financed by Farmers' Home Administration because bankers didn't want to make rural loans.

The house didn't have electricity until some big-government liberal stuck his nose where it didn't belong and demanded rural electrification.

He is happy to see his father, who is now retired. His father lives on Social Security and a union pension because some wine-drinking, cheese-eating liberal made sure he could take care of himself so Joe wouldn't have to.

Joe gets back in his car for the ride home, and turns on a radio talk show. The radio host keeps saying that liberals are bad and conservatives are good. He doesn't mention that the beloved Republicans have fought against every protection and benefit Joe enjoys throughout his day. Joe agrees: "We don't need those big-government liberals ruining our lives! After all, I'm a self-made man who believes everyone should take care of themselves, just like I have."

Added in January 2022:

Of all the deniers, it's the pilots who make me the craziest.

When you fly, you are totally in the hands of the government. You fly aircraft that are FAA-certified for safety, and maintained by FAA-certified mechanics to FAA-mandated standards. You are relying on FCC-regulated radio frequencies to communicate with FAA-trained controllers to navigate FAA-designated airspace. If, in spite of all of this, bad things happen, FAA investigators will arrive on scene and generate the official report.

We are trained by FAA-licensed instructors, pass FAA-mandated exams, and are signed off by FAA-designated examiners. Our health is closely monitored by FAA-accredited flight doctors. In every aspect of flight, we follow the Federal Air Regulations and a complex ballet of procedures that are required by custom and government fiat.

While we're in the air, we're utterly dependent on a government-built network of GPS satellites and VOR stations for navigation; USGS-generated charts for terrain, route, and waypoint info; and NOAA weather data to stay out of weather that could kill us. If we go down, odds are good it will be a government somewhere responding to our rescue beacon.

While all of us bitch about this, there's not one of us who'd rather be in a sky that didn't include it — even the biggest Trumper. Every one of those air regulations was written in human blood. Conservative pilots who think they'd be better off without Big Gummint on their back have not thought this one all the way through.

Friday, January 28, 2022

ANS -- a statistic.

Thursday, January 27, 2022

ANS -- A Sermon: Renewing My Unitarian Universalism by Doug Muder

F&RS is the philosophical/religious blog of Doug Muder. Its title comes from "a free and responsible search for truth and meaning," the 4th principle of Unitarian Universalism. You can find Doug's weekly political summary at The Weekly Sift and his longer political articles at Open Source Journalism. He also writes on a number of group blogs under the pseudonym Pericles.

Doug's Other Writing

Blog Archive

About Me

- DOUG MUDER

- Doug Muder blogs about religion (Free and Responsible Search) and politics (The Weekly Sift). He writes a bimonthly column for the magazine UU World. Doug lives in Nashua, NH with his wife Deb Bodeau.

TUESDAY, JANUARY 25, 2022

Renewing My Unitarian Universalism

presented in a Zoom session of the Unitarian Church of Quincy, Illinois

January 23, 2022

First Reading

In his 1915 novel Of Human Bondage, William Somerset Maugham wrote:

A Unitarian very earnestly disbelieves in almost everything that anybody else believes. And he has a very lively sustaining faith in he doesn't quite know what.

Second Reading

In 2012, April Fools Day fell on a Sunday. So Rev. Erika Hewitt preached a sermon on UU jokes. She started out by telling a few:

Each religion has its own Holy Book: Judaism has the Torah, Islam has the Koran, Christianity has the Bible, and Unitarian Universalism has Roberts' Rules of Order.

But eventually she raises the same issue Maugham had poked at almost a century before:

Our tolerance – or penchant – for ambiguous theology intersects with what I believe is the most egregious UU stereotype: that we are a faith with no core religious message.

When it comes to defining who we are as an Association and what we believe as individuals, our answers rarely satisfy.

Question: What happens when you cross a UU with a Jehovah's Witness?

Answer: They knock on your door, but they have no idea why!

We're even mocked on "The Simpsons." On one episode, the Simpson family attends a church ice cream social, where Lisa is impressed by the choice of ice cream available. "Wow," she raves, "look at all these flavors! Blessed Virgin Berry, Command-Mint, Bible Gum...."

"Or," Reverend Lovejoy says, "if you prefer, we also have Unitarian ice cream." He hands Lisa an empty bowl. "There's nothing here," says Lisa. "Exactly," says Lovejoy.

But by the end of her sermon, Hewitt isn't laughing any more:

There comes a point, for me, at which jokes like these cease to be funny by virtue of their volume and ubiquity — and the truth that they hold. Isn't it so, after all, that we continue to define ourselves by who we aren't rather than who we are? Isn't it true we're rendered tongue-tied when friends or co-workers ask us, "What do UU's believe?" …

I don't want our distinguished liberal religious movement to be portrayed as an empty bowl. … I don't want to belong to a faith where you can believe anything you want, and change your mind anytime you need to. Our beliefs will change throughout our lives; we're never "done" learning. But religious faith is not disposable. I don't want to be laughed at; I want to co-create a faith that garners respect.

Third Reading

One sign of old age is when you start using your own writings as readings. It's an admission that your past has become so distant that your own memory of it should no longer be trusted. If you wrote something down at the time, that's probably more accurate.

This reading is taken from a column I wrote for UU World called "At My Mother's Funeral". My mother died in 2011. The funeral was at Hansen-Spear, and I came back to Quincy for it. Mom had chosen all the elements of the service herself, so it reflected her Christian belief that death is just the beginning of eternal life in Heaven. I had trouble relating to that.

Here's what I wrote afterwards:

Whether anyone else in the room was harboring secret doubts or not, I felt alone in facing the possibility that death is final, that I will never see my mother again, that our interrupted conversations will never be finished, and that all the things we didn't understand about each other will never be understood.

Somewhere in the middle of those reflections, I almost laughed at myself: "Wait a minute," I thought. "I'm the Unitarian Universalist in the room. I'm supposed to be the one who can believe whatever he wants!"

Over the years I've probably heard a dozen UU ministers' explanations of why the old saw "Unitarian Universalists can believe whatever they want" isn't quite right. But until that moment at Mom's funeral, I had never grasped how exactly backwards it is.Unitarian Universalists are precisely the people who can't believe whatever they want.

The image of Mom in heaven — young and vibrant again, seeing everything, hearing everything, skipping gaily about on two perfect legs — how could anyone not want to believe that?

The vision of heaven itself — a perfect place where all loved ones will reunite, and all pains and doubts and disagreements will be revealed as the illusions they always were: I don't want to reject it, I just can't sustain it. Like a multistory house of cards, it always collapses before I can get it finished. …

The old religious authorities taught … [that] people needed someone or something to keep their beliefs in line. Otherwise they'd believe all kinds of frivolous, self-serving, and wish-fulfilling things.

But is frivolity, self-service, and wish fulfillment what Unitarian Universalism is about? Is that what I was doing at the funeral?

No, quite the opposite. Today's Unitarian Universalists continue to be free of external discipline, but the point is to be self-disciplined, not un-disciplined. We're the people who take responsibility for disciplining our own beliefs.

Like any other responsibility, religious responsibility is a two-edged sword. On the one hand, my beliefs feel more straightforward and authentic because I haven't twisted them to fit some external authority's template. But on the other, I am cut off from the comforts of frivolous, self-serving, and wish-fulfilling beliefs, because no one can authorize them for me.

Sermon

Coming of Age. Every year, if we have enough interested kids of the right ages, my church (First Parish in Bedford, Massachusetts), offers a "Coming of Age" class. Starting in September, our teens explore what it means to be a Unitarian Universalist. They learn UU history, do service projects, hear what famous UUs have said about the big questions, and interview members of the congregation. And then in May, the program culminates in a service that turns the traditional Protestant confirmation ritual upside-down.

When I was confirmed at St. James in 1970, my classmates and I had to demonstrate that we understood the teachings of the Lutheran church, and in the spring we solemnly affirmed to the whole congregation that we agreed with them.

A UU coming-of-age service, by contrast, focuses on the young people's beliefs, not the congregation's. One by one, they stand in the pulpit and present a personal credo. In other words, they preach to us about their deepest convictions.

It's always an engaging service, largely because there's no predicting what you'll hear. One of the teens might believe in reincarnation, another is inspired by Zen, and a third is a hard-core rationalist. Some are optimists and others pessimists. Some think the purpose of life is to pursue happiness, while others focus on serving others. Some want to create beauty; others want to acquire knowledge and solve problems.

My Lutheran confirmation was about pledging to remain steadfast in the common faith, a promise that I was unable to keep. If anyone had realized at the time how much my beliefs would change in the next few years, and keep changing for decades after, I imagine that thought would have depressed them. It would have undermined the meaning of the whole ritual.

But the adults who attend our UU coming-of-age service look back on our own religious journeys, and anticipate that the beliefs we're hearing will change. Ten years down the road, the young man who tells us about reincarnation may not remember why he said that. The young woman who intends to center her life on pursuing happiness may someday come to a place where happiness seems impossible. She may need to find inside herself a grit and determination that has little to do with happiness, but that will see her through to a time when happiness once again becomes a viable goal.

But anticipating those changes doesn't make the service any less moving or inspiring, because we understand the commitment that the young people are really making. They aren't pledging to believe these things for the rest of their lives, a promise they would almost certainly break. Rather, they're committing to take responsibility for their beliefs.

Alone up there in the pulpit, they can't hide behind their parents or the church or a creed or a holy book or even God. They are announcing: "At this moment, this is how I choose to approach my life. And if those choices have consequences, they're on me."

It's a brave thing to do.

Watching young people construct their own version of Unitarian Universalism always makes me want to reconstruct mine. And that's what I want to talk about today: How my own beliefs have had to change, not just until I became a UU, but since I became a UU.

Freedom and responsibility. Probably the most significant thing I've had to reevaluate about my faith is the centrality of freedom. Our Fourth Principle affirms "a free and responsible search for truth and meaning". But when I was becoming a UU in the 1980s, freedom got way more emphasis than responsibility. The most important feature of UUism then wasn't a presence, it was an absence: No one would tell you what you had to think. (That's why we might have appeared from the outside to have a lively, sustaining faith in we know not what.)

That emphasis made sense for the kind of world I grew up in, where my family, my church, the teachers at St. James school, and American culture itself were all trying to imprint Christianity on me. To me, the outside world seemed like a unified oppressive force trying to squelch my capacity for independent thought.

Saying "no" to that, saying "I am going to live by the faith I actually have, rather than the faith everyone tells me I ought to have" was a revolutionary act. And I saw that revolution as a precondition for everything else. Until I had staked out and defended my spiritual and intellectual independence, it didn't even matter what I believed in my heart of hearts. Because if I'm going to spend my life reciting the Apostles Creed, and pretending to believe it, who even cares what I really think?

But the kids in our coming of age classes don't live in that world. And while some young people do still grow up in oppressive religious environments, that's no longer the general experience of American society.

Yes, conservative Christians still aspire to dominance, and try to make laws that impose their faith on the rest of us. But that effort gets increasingly desperate every year. They need the power of government now, and especially the power of unelected judges, because they lost the battle for the larger culture long ago.

For most young Americans today, and particularly for those who have grown up UU, the outside world does not feel like a monolithic force trying to control their minds. It's more like a desert or even a vacuum. The threat outside the walls of the church is not that some Eye of Sauron will dominate them, it's that they will wander out there and get lost in the trackless waste where nothing is true and nothing is known and nothing is more important than anything else. When you find yourself in a trackless waste, no one needs to remind you that you are free to go any direction you want. What needs to be affirmed is that there are places worth going, and some hope of getting there.

In the current environment, it can actually be dangerous to tell people that they can believe whatever they want, because look around — lots of people are doing precisely that, to an extent that the UUs of the 1980s never imagined.

Do you want to believe that your candidate won the election when every method of counting the votes says that he lost? Go for it. Do you want to believe that Covid is a global conspiracy? Why not? Do you want to believe that your political opponents are blood-drinking, child-abusing Satanists? Or reptilian aliens? It's up to you. There are no facts, just "I want to believe this and you want to believe that."

That kind of freedom isn't what Unitarian Universalism is about, or has ever been about. When our kids consider what they mean by the word "God", and discuss whether such a God exists, they're doing something very different from the QAnon folks who assure each other that JFK Jr. is going to return from his apparent death and lead them in a bloody counter-revolution.

The difference is in the responsible part of our free and responsible search. Our beliefs aren't just for our own entertainment. If we hold our beliefs responsibly, they change how we live. And if we live actively, the effects of those beliefs go out into the world, benefiting some people and perhaps harming others. And we're responsible for those benefits and harms. It's on us.

Wanting to believe. Think about climate change. Do I want to believe that the planet is getting warmer, and that rising temperatures will have devastating effects unless we all make serious changes? Of course not. If I could snap my fingers and make that not be true, I would. You all would.

Am I free to deny global warming? I suppose so. If I say it's all a hoax, and start living as if burning fossil fuels isn't a problem, nobody's going to punish me. But I'm not just free, I'm responsible. Living that way has consequences, and I have to take those consequences seriously.

Or think about privilege. I benefit from a long list of privileges. I'm White, male, heterosexual, cisgender, native born, neurotypical, English speaking, and professional class. I'm not just educated, I got my education at a time when it was cheaper, so I didn't have to pile up student debt.

Do I want to acknowledge all those unearned advantages? Not at all. I want to say that everything I have comes entirely from my own talent and hard work. And I'm free to say that.But to the extent that I promote the myth that the world is already just, the continuing injustice becomes my responsibility.

In a world dominated by oppressive belief systems, the most important thing about Unitarian Universalism is the freedom it offers to develop your own conscience and pursue your own goals. But in American society as I see it today, the most important thing to emphasize is the responsibility of our search.

By contrast, much of what passes for religion in America today enables irresponsibility. Too many churches are like money-laundering banks. They shield their members from the ugly consequences of self-serving beliefs.

Imagine, for example, that I am a young man looking for a wife. If I tell the women I meet that I intend to dominate, and that after we are married, I will decide what she can and can't do with her life, I sound like a jerk.

But suppose I say instead that my church believes in the traditional family. God has a plan for us all, and that plan has separate lanes for men and women. The content and consequence of those beliefs are exactly the same, but my responsibility for them vanishes. Now I'm not a jerk, I'm a man of faith. And if being dominated doesn't make you happy, don't blame me, blame God.

Or suppose that I want to persecute gays and lesbians, or maintain White supremacy. I don't have to account for damage those ideas do. I can find a church that holds those beliefs for me, one that emphasizes the parts of the Bible I like, and interprets them in ways that please me. And suddenly I am no longer hateful, I'm just devout. I make the choices, but God bears the responsibility.

Unitarian Universalism doesn't provide that service. It won't launder the dirty consequences of your ideas and leave you spotless. If your beliefs cause harm in the world, that's on you. It's not the church or some prophet or priest. It's not a creed or a holy book, and it's certainly not God. It's you.This is a faith for people who take responsibility.

On the elevator. One of the exercises we always have the coming-of-age students do is to write an elevator speech. The idea is that you're on an elevator when someone asks you what your religion is all about. What can you manage to say about UUism before the doors open and you go your separate ways?

UUs are particularly bad at this exercise, because we always want to include a few more caveats and nuances. In all the times I've been involved with coming of age, I've never come up with an elevator speech I liked.

Until now. Here it is:

Unitarian Universalists take responsibility for disciplining our own beliefs so that they are factual, reasonable, just, and kind. We will not stop learning, growing, and changing until we become the people the world needs.

Credo. Having come this far, I might as well close by completing the coming-of-age exercises and presenting my credo. So far I've mainly talked about how UUs believe, and haven't said much about the content of my personal beliefs.

So here it goes: This what I believe.

I believe that the Universe is far bigger and more intricate than human minds can grasp, and that we deal with that deficiency by telling stories. But the Universe is not a story, so we will never get it completely right. Nonetheless, I constantly try to improve my stories by testing them against observable facts, and changing them when they conflict.

I judge right and wrong by human standards. Things are good or bad according to how they affect people and other conscious beings, and not because some book or institution says so.

I give precedence to the things I know, rather than the things I merely imagine. So while I sometimes have intuitions about higher intelligences or what might happen after death, I hold those beliefs so lightly that they have little effect on my actions.

I believe meaning is something that stories have, and so I look for a meaningful life by striving to tell a meaningful life story. A meaningful story has to be credible, which is why integrity is so important; I believe in trying to be the person I say I am.

A good story evokes awe and wonder, so it is important that I find and create beauty in my life. The variety of beauty I personally resonate with most is the beauty of knowledge and ideas, which is why I put so much effort into understanding what is happening around me. Other people resonate primarily with other forms of beauty, and that's fine. We don't all need to be the same.

A story is more convincing when it is shared, when many people tell similar stories about similar things. And so it is important that I not be the only significant character in my story. I want to share my life with others, and to live in a community of people who care about and appreciate each other.

Nothing undoes the beauty of a story quite so effectively as a sense of hidden evil, of questions that we dare not ask and doors that we dare not open, lest all that hidden ugliness spill out. And so I believe in justice. I believe in looking squarely at the evil in the world and trying to fix it, rather than hiding it away and pretending it's not there.

And finally, I believe I'm going to die, probably at some unpredictable moment, and that everyone I care about will die someday as well. Any organizations I might join will someday fail. Cultures will change. Civilizations will collapse. And ultimately the Universe itself will go cold. So the satisfaction invoked by my life story can't depend on a happy ending.

Fortunately, it doesn't need to. I don't need a story that lasts forever, I only need one I that stays meaningful until I die, and that is not undone by the prospect of my death. In other words, I need my story to be part of a larger story that will continue past my death in the stories of others, in the story of my community, and in the larger story of the struggle to understand the world and achieve justice. That is the kind of life I am trying to live and the story I am trying to tell.

And you? That's me. But this is Unitarian Universalism, so you are free to disagree with any of that. Nonetheless I invite and encourage all of you to examine your own lives, your own stories, and your own beliefs.

Deciding who you're going to be is not just a job for teen-agers. Periodically throughout our lives, I think, we need to renew our sense of who we are, how we're going to live, and what we think about the world we live in.

I wish you well in your free and responsible search for truth and meaning.

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

Fwd: Why does this not surprise me..........

From:

Date: Tue, Jan 25, 2022 at 9:53 AM

Subject: Why does this not surprise me..........

To:

Sunday, January 23, 2022

ANS -- Human History Gets a Rewrite

Human History Gets a Rewrite

A brilliant new account upends bedrock assumptions about 30,000 years of change.

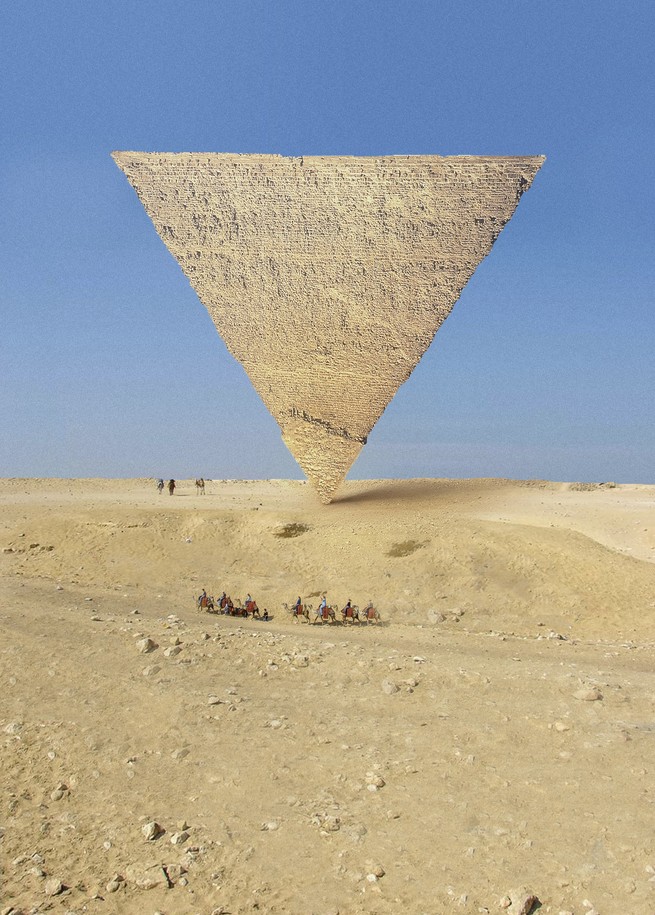

Illustration by Rodrigo Corral. Sources: Hugh Sitton / Getty; Been There YB / Shutterstock

Illustration by Rodrigo Corral. Sources: Hugh Sitton / Getty; Been There YB / ShutterstockMany years ago, when I was a junior professor at Yale, I cold-called a colleague in the anthropology department for assistance with a project I was working on. I didn't know anything about the guy; I just selected him because he was young, and therefore, I figured, more likely to agree to talk.

FROM OUR NOVEMBER 2021 ISSUE

Check out the full table of contents and find your next story to read.

Five minutes into our lunch, I realized that I was in the presence of a genius. Not an extremely intelligent person—a genius. There's a qualitative difference. The individual across the table seemed to belong to a different order of being from me, like a visitor from a higher dimension. I had never experienced anything like it before. I quickly went from trying to keep up with him, to hanging on for dear life, to simply sitting there in wonder.

That person was David Graeber. In the 20 years after our lunch, he published two books; was let go by Yale despite a stellar record (a move universally attributed to his radical politics); published two more books; got a job at Goldsmiths, University of London; published four more books, including Debt: The First 5,000 Years, a magisterial revisionary history of human society from Sumer to the present; got a job at the London School of Economics; published two more books and co-wrote a third; and established himself not only as among the foremost social thinkers of our time—blazingly original, stunningly wide-ranging, impossibly well read—but also as an organizer and intellectual leader of the activist left on both sides of the Atlantic, credited, among other things, with helping launch the Occupy movement and coin its slogan, "We are the 99 percent."

On September 2, 2020, at the age of 59, David Graeber died of necrotizing pancreatitis while on vacation in Venice. The news hit me like a blow. How many books have we lost, I thought, that will never get written now? How many insights, how much wisdom, will remain forever unexpressed? The appearance of The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity is thus bittersweet, at once a final, unexpected gift and a reminder of what might have been. In his foreword, Graeber's co-author, David Wengrow, an archaeologist at University College London, mentions that the two had planned no fewer than three sequels.

And what a gift it is, no less ambitious a project than its subtitle claims. The Dawn of Everything is written against the conventional account of human social history as first developed by Hobbes and Rousseau; elaborated by subsequent thinkers; popularized today by the likes of Jared Diamond, Yuval Noah Harari, and Steven Pinker; and accepted more or less universally. The story goes like this. Once upon a time, human beings lived in small, egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers (the so-called state of nature). Then came the invention of agriculture, which led to surplus production and thus to population growth as well as private property. Bands swelled to tribes, and increasing scale required increasing organization: stratification, specialization; chiefs, warriors, holy men.

Eventually, cities emerged, and with them, civilization—literacy, philosophy, astronomy; hierarchies of wealth, status, and power; the first kingdoms and empires. Flash forward a few thousand years, and with science, capitalism, and the Industrial Revolution, we witness the creation of the modern bureaucratic state. The story is linear (the stages are followed in order, with no going back), uniform (they are followed the same way everywhere), progressive (the stages are "stages" in the first place, leading from lower to higher, more primitive to more sophisticated), deterministic (development is driven by technology, not human choice), and teleological (the process culminates in us).

It is also, according to Graeber and Wengrow, completely wrong. Drawing on a wealth of recent archaeological discoveries that span the globe, as well as deep reading in often neglected historical sources (their bibliography runs to 63 pages), the two dismantle not only every element of the received account but also the assumptions that it rests on. Yes, we've had bands, tribes, cities, and states; agriculture, inequality, and bureaucracy, but what each of these were, how they developed, and how we got from one to the next—all this and more, the authors comprehensively rewrite. More important, they demolish the idea that human beings are passive objects of material forces, moving helplessly along a technological conveyor belt that takes us from the Serengeti to the DMV. We've had choices, they show, and we've made them. Graeber and Wengrow offer a history of the past 30,000 years that is not only wildly different from anything we're used to, but also far more interesting: textured, surprising, paradoxical, inspiring.

The bulk of the book (which weighs in at more than 500 pages) takes us from the Ice Age to the early states (Egypt, China, Mexico, Peru). In fact, it starts by glancing back before the Ice Age to the dawn of the species. Homo sapiens developed in Africa, but it did so across the continent, from Morocco to the Cape, not just in the eastern savannas, and in a great variety of regional forms that only later coalesced into modern humans. There was no anthropological Garden of Eden, in other words—no Tanzanian plain inhabited by "mitochondrial Eve" and her offspring. As for the apparent delay between our biological emergence, and therefore the emergence of our cognitive capacity for culture, and the actual development of culture—a gap of many tens of thousands of years—that, the authors tell us, is an illusion. The more we look, especially in Africa (rather than mainly in Europe, where humans showed up relatively late), the older the evidence we find of complex symbolic behavior.

That evidence and more—from the Ice Age, from later Eurasian and Native North American groups—demonstrate, according to Graeber and Wengrow, that hunter-gatherer societies were far more complex, and more varied, than we have imagined. The authors introduce us to sumptuous Ice Age burials (the beadwork at one site alone is thought to have required 10,000 hours of work), as well as to monumental architectural sites like Göbekli Tepe, in modern Turkey, which dates from about 9000 B.C. (at least 6,000 years before Stonehenge) and features intricate carvings of wild beasts. They tell us of Poverty Point, a set of massive, symmetrical earthworks erected in Louisiana around 1600 B.C., a "hunter-gatherer metropolis the size of a Mesopotamian city-state." They describe an indigenous Amazonian society that shifted seasonally between two entirely different forms of social organization (small, authoritarian nomadic bands during the dry months; large, consensual horticultural settlements during the rainy season). They speak of the kingdom of Calusa, a monarchy of hunter-gatherers the Spanish found when they arrived in Florida. All of these scenarios are unthinkable within the conventional narrative.

Five minutes into my lunch with David Graeber, I realized that I was in the presence of a genius. Not an extremely intelligent person—a genius.The overriding point is that hunter-gatherers made choices—conscious, deliberate, collective—about the ways that they wanted to organize their societies: to apportion work, dispose of wealth, distribute power. In other words, they practiced politics. Some of them experimented with agriculture and decided that it wasn't worth the cost. Others looked at their neighbors and determined to live as differently as possible—a process that Graeber and Wengrow describe in detail with respect to the Indigenous peoples of Northern California, "puritans" who idealized thrift, simplicity, money, and work, in contrast to the ostentatious slaveholding chieftains of the Pacific Northwest. None of these groups, as far as we have reason to believe, resembled the simple savages of popular imagination, unselfconscious innocents who dwelt within a kind of eternal present or cyclical dreamtime, waiting for the Western hand to wake them up and fling them into history.

The authors carry this perspective forward to the ages that saw the emergence of farming, of cities, and of kings. In the locations where it first developed, about 10,000 years ago, agriculture did not take over all at once, uniformly and inexorably. (It also didn't start in only a handful of centers—Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, Mesoamerica, Peru, the same places where empires would first appear—but more like 15 or 20.) Early farming was typically flood-retreat farming, conducted seasonally in river valleys and wetlands, a process that is much less labor-intensive than the more familiar kind and does not conduce to the development of private property. It was also what the authors call "play farming": farming as merely one element within a mix of food-producing activities that might include hunting, herding, foraging, and horticulture.

Settlements, in other words, preceded agriculture—not, as we've thought, the reverse. What's more, it took some 3,000 years for the Fertile Crescent to go from the first cultivation of wild grains to the completion of the domestication process—about 10 times as long as necessary, recent analyses have shown, had biological considerations been the only ones. Early farming embodied what Graeber and Wengrow call "the ecology of freedom": the freedom to move in and out of farming, to avoid getting trapped by its demands or endangered by the ecological fragility that it entails.

From the December 2020 issue: The next decade could be even worse

The authors write their chapters on cities against the idea that large populations need layers of bureaucracy to govern them—that scale leads inevitably to political inequality. Many early cities, places with thousands of people, show no sign of centralized administration: no palaces, no communal storage facilities, no evident distinctions of rank or wealth. This is the case with what may be the earliest cities of all, Ukrainian sites like Taljanky, which were discovered only in the 1970s and which date from as early as roughly 4100 B.C., hundreds of years before Uruk, the oldest known city in Mesopotamia. Even in that "land of kings," urbanism antedated monarchy by centuries. And even after kings arose, "popular councils and citizen assemblies," Graeber and Wengrow write, "were stable features of government," with real power and autonomy. Despite what we like to believe, democratic institutions did not begin just once, millennia later, in Athens.

If anything, aristocracy emerged in smaller settlements, the warrior societies that flourished in the highlands of the Levant and elsewhere, and that are known to us from epic poetry—a form of existence that remained in tension with agricultural states throughout the history of Eurasia, from Homer to the Mongols and beyond. But the authors' most compelling instance of urban egalitarianism is undoubtedly Teotihuacan, a Mesoamerican city that rivaled imperial Rome, its contemporary, for size and magnificence. After sliding toward authoritarianism, its people abruptly changed course, abandoning monument-building and human sacrifice for the construction of high-quality public housing. "Many citizens," the authors write, "enjoyed a standard of living that is rarely achieved across such a wide sector of urban society in any period of urban history, including our own."

And so we arrive at the state, with its structures of central authority, exemplified variously by large-scale kingdoms, by empires, by modern republics—supposedly the climax form, to borrow a term from ecology, of human social organization. What is the state? the authors ask. Not a single stable package that's persisted all the way from pharaonic Egypt to today, but a shifting combination of, as they enumerate them, the three elementary forms of domination: control of violence (sovereignty), control of information (bureaucracy), and personal charisma (manifested, for example, in electoral politics). Some states have displayed just two, some only one—which means the union of all three, as in the modern state, is not inevitable (and may indeed, with the rise of planetary bureaucracies like the World Trade Organization, be already decomposing). More to the point, the state itself may not be inevitable. For most of the past 5,000 years, the authors write, kingdoms and empires were "exceptional islands of political hierarchy, surrounded by much larger territories whose inhabitants … systematically avoided fixed, overarching systems of authority."

Is "civilization" worth it, the authors want to know, if civilization—ancient Egypt, the Aztecs, imperial Rome, the modern regime of bureaucratic capitalism enforced by state violence—means the loss of what they see as our three basic freedoms: the freedom to disobey, the freedom to go somewhere else, and the freedom to create new social arrangements? Or does civilization rather mean "mutual aid, social co-operation, civic activism, hospitality [and] simply caring for others"?

These are questions that Graeber, a committed anarchist—an exponent not of anarchy but of anarchism, the idea that people can get along perfectly well without governments—asked throughout his career. The Dawn of Everything is framed by an account of what the authors call the "indigenous critique." In a remarkable chapter, they describe the encounter between early French arrivals in North America, primarily Jesuit missionaries, and a series of Native intellectuals—individuals who had inherited a long tradition of political conflict and debate and who had thought deeply and spoke incisively on such matters as "generosity, sociability, material wealth, crime, punishment and liberty."

The Indigenous critique, as articulated by these figures in conversation with their French interlocutors, amounted to a wholesale condemnation of French—and, by extension, European—society: its incessant competition, its paucity of kindness and mutual care, its religious dogmatism and irrationalism, and most of all, its horrific inequality and lack of freedom. The authors persuasively argue that Indigenous ideas, carried back and publicized in Europe, went on to inspire the Enlightenment (the ideals of freedom, equality, and democracy, they note, had theretofore been all but absent from the Western philosophical tradition). They go further, making the case that the conventional account of human history as a saga of material progress was developed in reaction to the Indigenous critique in order to salvage the honor of the West. We're richer, went the logic, so we're better. The authors ask us to rethink what better might actually mean.

The Dawn of Everything is not a brief for anarchism, though anarchist values—antiauthoritarianism, participatory democracy, small-c communism—are everywhere implicit in it. Above all, it is a brief for possibility, which was, for Graeber, perhaps the highest value of all. The book is something of a glorious mess, full of fascinating digressions, open questions, and missing pieces. It aims to replace the dominant grand narrative of history not with another of its own devising, but with the outline of a picture, only just becoming visible, of a human past replete with political experiment and creativity.

"How did we get stuck?" the authors ask—stuck, that is, in a world of "war, greed, exploitation [and] systematic indifference to others' suffering"? It's a pretty good question. "If something did go terribly wrong in human history," they write, "then perhaps it began to go wrong precisely when people started losing that freedom to imagine and enact other forms of social existence." It isn't clear to me how many possibilities are left us now, in a world of polities whose populations number in the tens or hundreds of millions. But stuck we certainly are.

This article appears in the November 2021 print edition with the headline "It Didn't Have to Be This Way." When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.