Fascism, in Haque's view, is a political technique for gathering up the misery of the masses and focusing it on scapegoats rather than solutions. The primary promise of the fascist leader is revenge, which will solve the problems of his followers through some magical process of subtraction rather than addition. Throwing rocks through the windows of Jewish businesses or preventing trans kids from getting gender-affirming care will somehow make your own life better. Break up the families of migrants seeking asylum, and somehow your own inability to care for your sick wife or send your children to college will not hurt so much.

|

Why fascism? Why now?

We spend a lot of time thinking about how fascism is rising, but not nearly enough about why.

Week after week, I find myself chronicling the signs of a rising fascism, both in the United States and around the world: the January 6 insurrection (and the attempts to write it off as no big deal), the parallel Bolsonaro riot in Brazil, Governor Abbott's offer to pardon a conservative for murdering a liberal protester, increasing state violence in India ("politicians are learning that violence can yield political dividends in a country deeply polarized along religious lines"), refusal to accept that electoral defeat can be legitimate, defense of treason if it supports your cause ("Jake Teixeira is white, male, christian, and antiwar. That makes him an enemy to the Biden regime. … Ask yourself who is the real enemy?"), the increasingly cynical abuse of right-wing political and judicial power, combined with a reflexive tolerance for right-wing corruption in high places. And so on. [1]

Examples of rising fascist tendencies easily draw attention and produce fear for the future. But much less attention gets focused on the deeper question: Why is this happening now? Fascism has never been completely stamped out, but for decades it was a fringe phenomenon. By and large, losing parties admitted their defeats, tacked back to the center, and tried to regain majority support rather than disenfranchise the voters who rejected them. Elected officials distanced themselves from violence, treason, and blatantly corrupt allies.

What changed? It can't just be the fault of one bad leader. How, for example, could Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin be causing a drift towards fascism in Europe or South America or India or Israel?

Recently I happened across two essays that address this question in different ways: science fiction author David Brin's "Isaac Asimov, Karl Marx, & the Hari Seldon Paradox" and Umair Haque's "The Truth About Our Civilization's Fascism Problem Is Even Worse Than You Think". I don't intend to broadly endorse either author (especially Haque, who in general seems far too negative and fatalistic for me), but both have insights that strike me as important.

The post-war "miracle". For both Haque and Brin, the key question isn't why fascism is rising now, but how it got pushed to the fringe for decades after World War II. Haque explains it like this:

Consider the founding of modern Europe. Its entire idea was to prevent the far right ever rising again. Modern Europe, rebuilt in the ashes of the war, did something remarkable, that led to what later observers like me would call the European Miracle. It took the relatively small amount of investment that America gave it — which was all it had — and used that in a way that was fundamentally new in human history. Instead of spending it on arms, or giving it to elites, it used it rewrite constitutions which guaranteed everything from healthcare to education to transport as basic, fundamental, universal rights.

This was the point of Keynes' magisterial insight into why the War had happened. Germans, declining into sudden poverty, destabilized by debt, had undergone a political implosion. Economic ruin had had political consequences. The consequences of "the peace" as Keynes said — the peace of World War I, which had been designed to keep Germany impoverished. Fascism erupted as a result. And so after the Second World War, Europe did something bold, unprecedented, and remarkable in all of human history — it offered its citizens these cutting edge social contracts, rich in rights for all, built institutions to enact them, from pension systems to high speed trains, and then formed a political union on top of that, to make sure that peace, this time, remained.

Fascism, in Haque's view, is a political technique for gathering up the misery of the masses and focusing it on scapegoats rather than solutions. The primary promise of the fascist leader is revenge, which will solve the problems of his followers through some magical process of subtraction rather than addition. Throwing rocks through the windows of Jewish businesses or preventing trans kids from getting gender-affirming care will somehow make your own life better. Break up the families of migrants seeking asylum, and somehow your own inability to care for your sick wife or send your children to college will not hurt so much.

America and England both had fascist movements in the 1930s, but they didn't catch on like Germany's. Maybe that was because — even in the depths of the Depression — neither country had Germany-level misery. Neither country experienced quite the sense of failure and loss of hope that made Hitler seem like a compelling way forward.

But Brin points to something else that happened in 1930s America: the New Deal, which confounded Karl Marx' prediction of ever-increasing dominance by wealthy capitalists, inevitably leading to a revolutionary explosion.

Karl Marx never imagined that scions of wealth – Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his circle – would be persuaded to buy off the workers, by leveling the field and inviting them to share in a strong Middle Class, whose children would then (as recommended by Adam Smith) be able to compete fairly with scions of the rich.

It was a stunning (if way-incomplete) act of intelligence and resilience that changed America's path and thus the world's.

Brin, recalling the lessons of Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, invokes the Seldon Paradox: "Accurate psychohistorical predictions, once made known, set into effect psychohistorical forces that falsify the prediction." In this case, American plutocrats like "that smart crook, Joseph Kennedy" took Marx' predictions seriously and tried to head them off. Brin quotes Kennedy: "I'd rather be taxed half my wealth so the poor and workers are calm and happy than lose it all to revolution."

Kennedy's view was far from universal among the American rich, but it did split the forces of plutocracy, enabling the creation of an American safety net.

Post-war Europe took the lesson further, as Haque describes:

What do Europeans enjoy, still, even though it's teetering now, that Americans don't? All those rich, sophisticated social contracts, one supposes, which guarantee them everything from high speed transport to cutting edge healthcare.

But there's more than that. All that creates — or did for a very long time — a feeling that doesn't exist in America. A sense of community. A kind of peace, which you can readily see in the absence of gun massacres in Europe, even though, yes, there are guns, if not quite so many. Stronger social bonds and ties — Europeans still have friends, and in America, friendship itself has become a luxury. All that matters.

The short description of what Europe achieved is public happiness.

Fascism is born of rage, fear, despair, which drives people into the arms of demagogues, who blame all those woes on hated subhumans, "others" — and so the truest antidote we know of to all that is human happiness itself.

Revenge, not hope. That observation explains one of the great mysteries of current American politics: why the GOP has no governing program. The party has a clear constituency: the non-college White working class, particularly in rural areas. So why are there no plans to do anything for them?

Think about it: expanding Medicaid to save not just the families of the working poor, but rural hospital systems as well; bringing broadband internet to rural areas; raising the minimum wage; shoring up community colleges — those are all Democratic goals that Republicans do their best to block.

It's not that Republicans have no proposals. The red-state legislatures they control are buzzing with activity: loosening gun laws, taking away women's bodily autonomy, banning accurate accounts of racism from schools, defunding libraries, and making trans youth invisible, just to name a few.

But how exactly does that help anybody?

Or take that frequent Trump claim that "They're not after me, they're after you. I'm just in the way." Who is after you? How did Trump ever stand in their way? Even a sympathetic NY Post columnist has no answer for that. He spins conspiracy theories of how the Deep State has been out to get Trump from the beginning, but what does any of that have to do with the "you" in Trump's statement?

What Trump offered "you" was revenge. Those people you hate: the Muslims, the queers, the immigrants, the Blacks, the educated "elite", and so on. He demeaned them, insulted them, made them suffer. He "owned the libs" and made them hopping mad in ways that you never could have managed on your own..

But he never did anything to improve your life, because that was never the point. It would, in fact, have been counterproductive, because MAGAism needs your misery. If you felt more secure, more hopeful, more capable of dealing with a changing world, then you wouldn't need revenge any more. And you wouldn't need Trump.

Beyond the Seldon Paradox. So what happened to public happiness? Now we bounce back to Brin, who quotes a corollary to the Seldon Paradox: After people adjust to dire predictions and cause them to fail, the next generation stops taking the predictions seriously. And then they come true.

In other words, what we are seeing now… a massive, worldwide oligarchic putsch to discredit the very same Rooseveltean social compact that saved their caste and allowed them to become rich… but that led to them surrounding themselves with sycophants who murmur flattering notions of inherent superiority and dreams of harems. Would-be lords, never allowing themselves to realize that yacht has sailed.

In other words: Marx? Who listens to Marx any more? All his nonsense predictions turned out to be laughably false.

So sometime in the 1970s, the plutocratic counter-revolution began. One turning point was the infamous Powell Memo, written in 1971 by future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The American system of free enterprise, he wrote, was under broad attack from socialist thinkers, and business leaders had been responding with "appeasement, ineptitude and ignoring the problem". Powell outlined a multi-faceted program to create a new intellectual climate in America, one more favorable to corporate power and the influence of big money.

Within ten years, Ronald Reagan was president, and the United States had embarked on an era of ever-lower taxes on the rich, restrictions on corporate regulation, and union-busting.

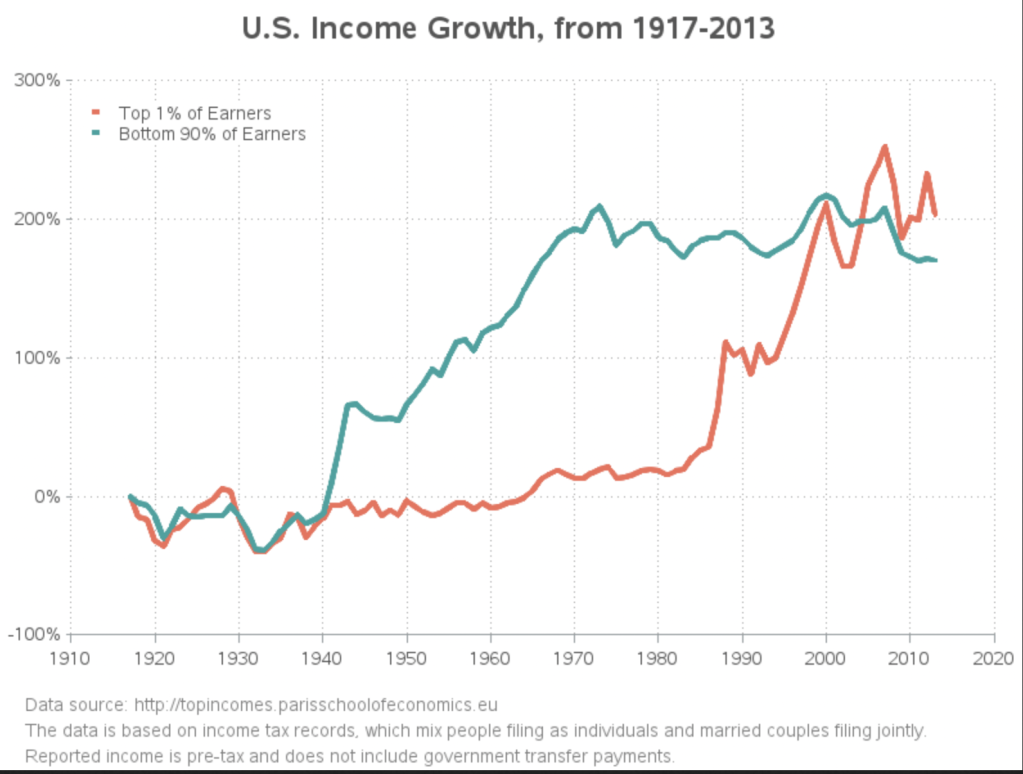

And that was the end of the great American middle class. From 1940 through 1980, income growth among the rich had lagged behind the larger public, but after the Reagan Revolution it rapidly made up the difference.

Then and now. A decline in human happiness and hope can lead to a Marxist revolution. (That was one possibility in Weimar Germany as well.) But it also creates opportunities for fascist scapegoating.

So if you don't feel as successful as your parents were at the same age, and you see even worse prospects waiting for your children, whose fault is that? Maybe it's the Jews. Maybe it's the November criminals who stabbed your valiant German soldiers in the back at Versailles. Maybe it's the decadent culture of big cities like Berlin: the gays, the transvestites, the young people dancing to that African "monkey music" from America.

If only we had a leader strong enough to make them pay.

See the resemblance?

Lessons. So where does that leave us? What lessons can we draw? One lesson is to keep our own resentment tightly focused on the people who deserve it. Working class Americans who see little hope for their children are not our enemies, even if they vote for our enemies. We shouldn't want revenge on them, we should want them to have better prospects, so that they lose their own need for revenge.

Us against Them is the fascist conversation. We can't let ourselves be drawn into it.

Our salvation will not come through their misery. Quite the reverse. If we are to be saved, it will have to be through happiness — everyone's happiness.

And if we're lucky, maybe some rebel faction of smart plutocrats will come to see the same thing.

[1] Some want to argue about whether to call this worldwide movement "fascism". I've explained why I do, but if you'd rather reserve the word for Hitler, Mussolini, et al, that's fine. Trump, Orban, and Bolsonaro are certainly not identical to Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco, but I would say that 20th-century fascism differs in some particulars from 21st-century fascism, not that they are completely different animals.

The important thing is that the lack of a word doesn't lead to an inability to discuss the phenomenon, in the fashion of Orwell's Newspeak. Simply referring to Trump, Orban, Bolsonaro, Modi, et al as "authoritarians" (as Tom Nichols does) is not nearly specific enough. Any general who stages a successful coup is an authoritarian. But an anti-democratic movement that anoints one segment of the citizenry as the "real" or "true" citizens, and scapegoats the "unreal" or "false" citizens as the cause of all the nation's problems, justifying discrimination and even violence against them — that's something more than just "authoritarianism".

In short, I'd be content to use some other word to carry on a discussion with someone who wants Hitler to be unique. But that word has to capture the full evil of the phenomenon, without diluting it by including anyone who finds democratic governance inefficient.

No comments:

Post a Comment