|

Dec 19, 2021

Rebalancing the Earth Is Dead Simple

We have made reversing climate change seem complex, expensive, and nearly insurmountable. In truth, it's dead simple. We are simply looking at the wrong equation.

Adisturbing multi-media Op-Ed I read today in the New York Times brings its readers to every country in the world, one by one, illustrating the tangible impacts of climate change in each. A majority of them are mired in continual catastrophe, while others face future collapses, while the clouds of early warning signs gather.

Record wildfires, droughts, storms, swarms, erosion, temperatures, floods, collapses, and mass die-offs are the rule now—not the exception. Nearly every nation on Earth is experiencing "unprecedented" everything, and not the good kind.

Collectively, the picture the Anthropocene paints is bleak. "Human-kind has caused mass extinctions of plant and animal species, polluted the oceans and altered the atmosphere, among other lasting impacts," per Smithsonian Magazine's rather dry description.

We've heard these things before—many times.

But not all the news is bleak. There is a glimmer of hope, buried about 150 countries into the NYT piece. A single sentence points the true way out of our quagmire.

"Most countries are struggling to become carbon neutral. Suriname, 93% of which is covered by forest, is one of three carbon-negative countries in the world."

After I read that, I looked up the other two. They are Bhutan and Panama. All three understand the three-step formula to long-term planetary health, and critically, they are all acting in accordance with its principles.

That is, they are doing it.

Healthy Earth in Three Steps

Step One: Maximize Reforestation

There are just three steps in fighting climate change. The first is: maximize reforestation. In his brilliant book Collapse, Jared Diamond brings readers through example after example of societies that cratered, then disappeared: the Anasazi, Rapa Nui, Greenland Norse, Maya, Polynesians, et al. In each subject population, chosen because it was self-contained, and thus scientifically "knowable", the primary driver of collapse was the same: the trees were cut down.

The title of a Nature article says it all: "No Trees… No Humans."

"No Trees… No Humans."

We have cut down half of the world's trees—three trillion of them—since we began practicing agriculture, 12,000 years ago. Of that total, two-thirds—or two trillion trees—have been felled in just 150 years, driven by financial gain and the Industrial Revolution.

In the Amazon—"the planet's counterweight to global warming", per Inside Climate News—ranchers like Jaim Teixeira are illegally setting fire to large swaths of it because A: it makes financial sense, and B: he'd rather eat today than save the world tomorrow.

The International Criminal Court in the Hague, Netherlands, has adopted a new crime among the world's gravest offenses—it's fifth, and the only one added since Hitler's Germany—called ecocide. Because the human effects of deforestation are catastrophic, the ICC has put ecocide on par with genocide. Brazil's Bolsonaro—who has poured accelerant over the practice of deforestation in the Amazon—stands to be the first to be found guilty of it.

As Diamond explains in his book, trees give shade to—and stabilize—the plants and soils beneath them. Once they're gone, they release the carbon they've sequestered from the atmosphere back into it. Once the plants that the trees shielded can no longer thrive, they, too, eventually die and also release their carbon. Once this happens, the Earth itself dries out, and the living things that depended on all of it also die.

Game over.

Sebastião Salgado, the world's greatest living photographer of war, famine, and genocide—and a personal hero of mine—told an audience in which I sat about what he'd learned in all of his years traveling every country on Earth. His answer:

"For all our fighting and wars over nothing, how long do you think we'd last once the last tree is gone? 30 seconds? 60?"

You could hear a pin drop in the room, as the gravity of his words settled.

He and his wife Lélia spent the next ten years back in his native Brazil repairing a 1,750-acre family farm that had been wiped out due to deforestation. They established the Instituto Terra. Two million trees later, a barren landscape now has 293 species of trees, 172 species of bird, 33 types of mammal, and 15 species of reptile/amphibian. As amazingly, water has returned to the land as well, to support all those trees and animals like every other healthy ecosystem on the planet.

All the Salgados did was plant trees.

In Uganda, Nathan Kyamanywa has begun a similar mission. Citing the same human drivers as those that drove other populations to extinction, he says, climate change "leaves [people] with two choices: development or survival."

The reason Suriname, Bhutan, and Panama are all carbon-negative is because the carbon that their forests sequester exceeds the total carbon produced by human activity. And so: if we were to do nothing but reforest large swaths of each country—enough to overcome our carbon production—climate change wouldn't exist.

Former Kenyan Member of Parliament Wangari Maathai said it beautifully:

"Until you dig a hole, you plant a tree, you water it and make it survive, you haven't done a thing. You are just talking."

Beyond reforestation, there are two other steps to achieving a rebalanced Earth.

Step Two: A Smaller Human Footprint

We have been lazy. We have invariably taken the easy route to meeting our (ever-growing) desires. We've spread out. We've done so because of a desire to maximize our own space, measured by acreage. On average, urban areas fit three people per every one person in "suburbia". If everyone lived in cities, without any other change to our lives, 75% of the current human residential footprint would either still be forest, or could be replanted as one, as the Salgados have done, by themselves, without special equipment, over 1,750 acres. The reparative impact to the environment would be immense.

Besides densifying our habitat, we could reconsider our farming practices. Two years ago, I wrote an article called Big Beef's Dirty Secrets. In it, I shared some data points:

- Agriculture uses 92% of the world's freshwater

- One-third of that goes to livestock, one half of which is for cattle alone

- It takes 1,800 gallons of water to grow one steak (by far the most of any food)

- Cattle consume 1,600 times more water than we drink

- Cattle are responsible for 70% of deforestation in the Amazon

- Deforestation produces 25% of all greenhouse gases

If we stopped eating cows alone, without making any other change to our diets, cities, or lives, fully one-third of all climate change would cease to be.

And it's not just cows. If agriculture uses 92% of the world's freshwater, modern farming—aquaponics, hydroponics, and aquaponics, specifically—are the solution to non-animal food. Hydroponics saves 70–90% of the water conventional farming soaks up. Aquaponics saves 90% of the same. And Aeroponics uses just 2% of the water of current agricultural practices.

Cue: vertical farming.

Vertical farms—aka modern greenhouses that use one of the three "ponics"—produce up to three hundred and forty times the yield of a conventional farm. To wit: an SF-area startup named Plenty uses AI-fueled lighting, watering, and temperature to produce 720 acres' worth of fruit and vegetables in just 2 acres.

it's only beginning.

Together, modern farming techniques can save 90-plus% of the water we use, on less than 1% of the land, if we focus on achieving the same yield in a smaller footprint.

That decision alone, without making any other changes to our lives and environmental impact, would allow us to repopulate nearly all of the land used by agriculture with forest.

Given that 38% of the global land surface is used for agriculture, of which one third is for cropland and two thirds for livestock, then mathematically we could readily save—and reforest—nearly one-third of the Earth's surface by using modern farming practices (which have the additional benefits of being year-round, pestilence-free, and of higher nutritional density) and by turning to pigs, sheep, chickens, goats, ducks and fish for our animal protein, and leaving the cows out of it.

To say it simply: to stop eating cows, employ modern techniques for farming, and reforest the land we recapture as a result of these things is to restore one-third of the planet. That's without touching the cars, buildings, energy production, suburban sprawl, waste or anything else we do to harm the Earth.

Step Three: Modernize Energy

Nearly everyone hyper-focuses on the use of produced energy—the fuel for our cars, buildings, and industry—without nearly any focus on the two things we've already covered (reforestation and food production/choices) that are at least as big a driver of climate change because if the Earth were strong enough to face our onslaught, it could "handle us".

Luckily, this third category of reversal is also simple today. The Earth (and the solar system) have always produced infinite energy sources, and we are now advanced enough to avail ourselves of all of them. In fact, while we think of sucking the Earth dry of its gas and oil are "lazy", they are nonetheless incredibly complex achievements of technological and human know-how. The only difference between those and renewables is that they are mature markets, whereas all of the other sources available to us—the Earth's own core heat, wind, water, and solar—are lagging behind in infrastructural investment. But unlike today's sources, to use so-called "green energy" is not to deplete anything. And once we get good at it, it will in all likelihood become less and less costly to do so.

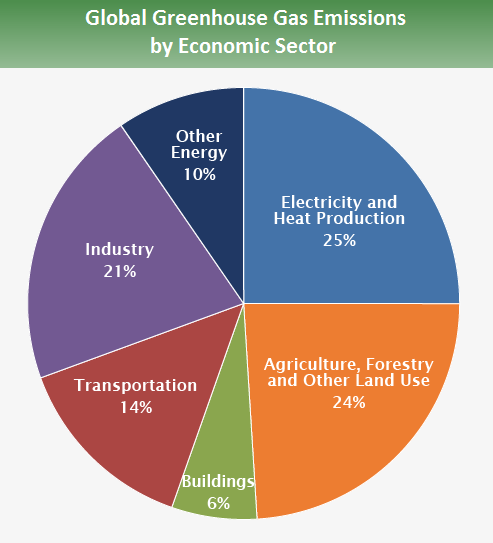

Transportation accounts for 14% of all greenhouse gas production, according to the EPA, while cars account for about half of that. If every person on Earth were to drive an electric vehicle, we would save the world from 7% of its warming.

A global fleet of electric cars would accomplish about 25% of what giving up beef would do for the planet.

Food for thought.

Nonetheless, 7% of planetary warming is important. Today, every major car manufacturer on Earth has electric vehicles for sale, everywhere. So, this piece of the puzzle isn't science fiction. It's simply a matter of choice and direct cost.

Though figures vary, the U.S. Government says that buildings use 76% of the world's electricity, and account for 40% of all energy use and greenhouse gas production. Admittedly, this is at odds with the U.S. Government's own chart, above, that lists buildings as contributing "just" 6% of it directly, plus perhaps 14% of the 25% consumed by heat and electricity production listed on the chart. So, let's call buildings at least 20% of the global problem.

We have known how to make buildings more energy-efficient for decades—if not centuries. 1: Create a high-performance envelope (the barrier between the outside climate and the inside one). 2: Use recycled and/or low-impact materials, which abound. 3: Use renewable energy like geothermal heat, solar energy, hydroelectric, or wind.

These strategies aren't necessarily cheap. But know this: if you do nothing else, pay for a "tighter" envelope, because 50% of the energy used by a building goes out of its "skin". Employ better construction techniques than the status quo, with better seals where building parts come together: windows, walls, doors, and roofs; and also higher insulation values for the materials and assemblies we use.

The German standard "Passivhaus" (Passive House) is laser-focused on building envelopes. In fact, it is the world's most stringent standard so far, and its principles are easy to follow. So, if you insist on shopping for steaks and burgers on field-grown buns in your gas-guzzling SUV, then eating them in your 2-acre suburban house, you can spend a little more on thicker insulation and better-sealed windows, and still do something to combat climate change.

Final Thoughts

There is an old joke about a lion who starts charging toward two safari tourists. One bends down to tie his shoe. The other screams, "You idiot! You'll never outrun a lion," to which his friend says, "I just need to outrun you."

The climate is a little bit like that, in reverse. We don't need to stop polluting it wholesale, or change everything about how humans live. We just need to do enough to slow ourselves down to let the Earth outrun us. That means acting more like Bhutan, Panama, and Suriname. Their cars aren't all electric; their buildings aren't all renewable; their food doesn't all come from vertical farms; they aren't vegan. In fact, probably little of what each nation does, apart from preserving or planting trees and doing less bad, is different from what richer nations are capable of doing much better. What all three countries are is balanced.

In each, more carbon is sequestered than is produced.

For this, they can thank the trees and the rich ecosystems that invariably follow. Just look at what the Salgados did.

The formula is straightforward: Shrink the human footprint (due to farming, livestock, and sprawl). Take that land and reforest it (as much as possible). Modernize energy (as much as you can afford to).

Shrink our footprint.

Reforest the land.

Modernize energy.

All three of these things—100%—are doable, and we have the technological and economic means at our disposal today. All we lack is the will to make choices that put some kind of limit on business as usual: what we eat; how we grow it; where we live, and in what; and what we drive.

The costs of our irresponsibility dwarf the investment it would take to reverse it later: in lost lives, in lost land, and in the true costs of mitigating strategies once living on Earth reaches a level of existential crisis.

Some would argue we are already there. Certainly, to the people in the New York Times Op-Ed videos, life-and-death struggles are now a daily occurrence.

Doing nothing is an incredibly expensive strategy.

An article I recently wrote for GEN was called Do No Harm. That was about human-to-human interaction, per se. But we could easily piggyback on it, and rename this article Do No Harm (That the Earth can't Absorb).

|

All we need to do is no more bad than that which the land itself can sustain, and counter-balance. This is the true genius of the NYT's Suriname example.

Dead simple, no???

No comments:

Post a Comment