BENJAMIN STUDEBAKER

Can We Fix Those Media Bias Charts?

by Benjamin Studebaker

Have you seen those charts that try to sort media outlets by political orientation? They have bothered me for years. They tend to use a single left/right scale, and they tend to position the centrist media as if it were "balanced" or "unbiased". When of course the reality is that the centrist press has its own position, one which is distinct from both the left and the right. So I've been thinking–can I make a chart that fixes this? Can we chart political orientation in a useful way?

Let me start by giving you an example of one of these charts, from AllSides.com:

The thing is, if you're a Jacobin reader, you know that Jacobin is not ideologically the same as The New York Times' opinion page. And if you're a Breitbart reader, you know Breitbart is not ideologically the same as National Review. New York Times is left liberal. Jacobin is socialist. National Review is libertarian right. Breitbart is alt-right. Jacobin loves Bernie Sanders. The NYT opinion page loved Clinton. National Review was full of never Trumpers. Breitbart was run by Steve Bannon. The fights that go on in American primaries are largely missed by this chart.

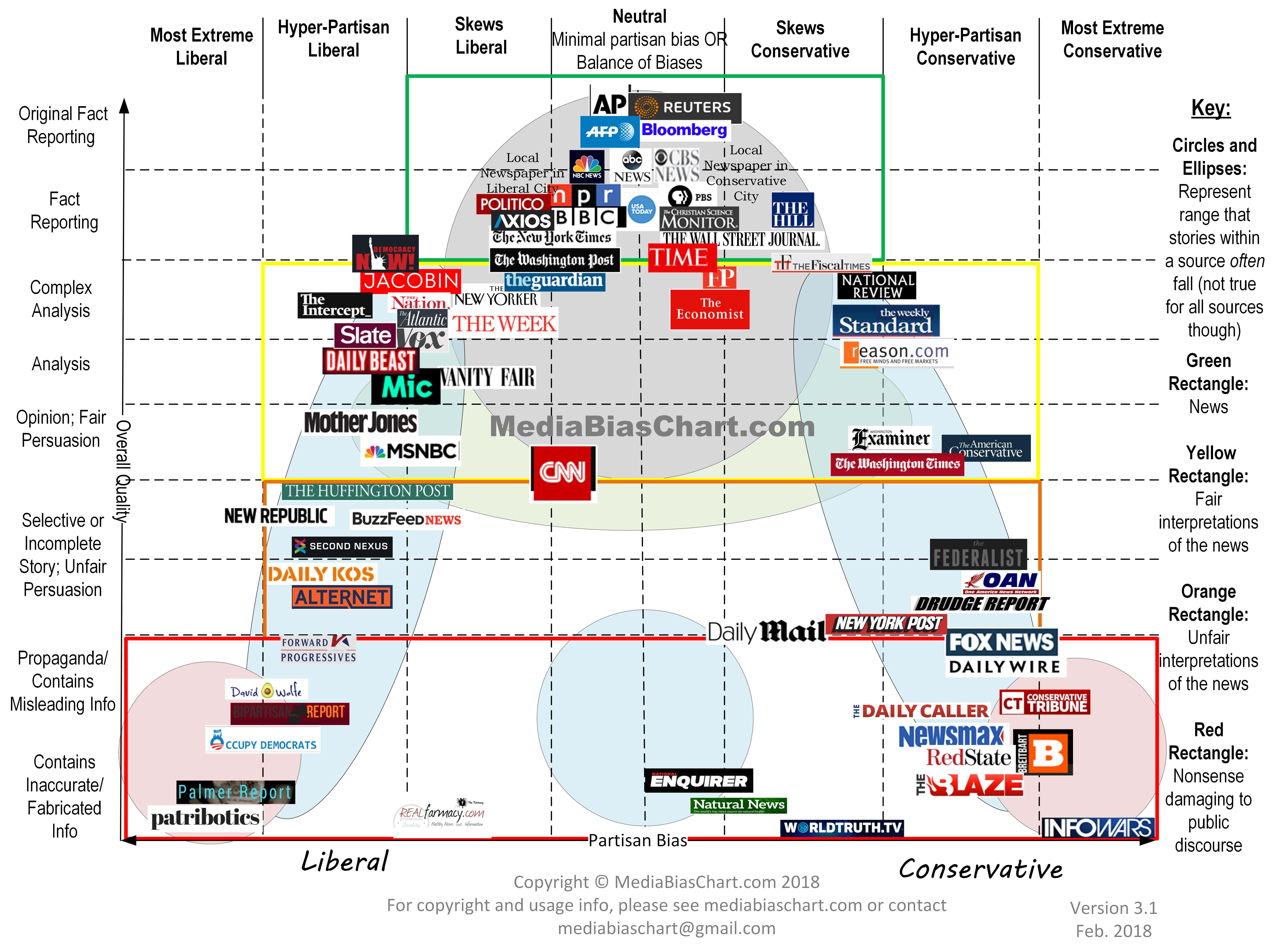

Here's another chart from Ad Fontes Media:

This chart commits the grievous sin of calling centrism "neutral", when it is itself a substantive basket of positions and ideas. Worse, it implies that the more you deviate from the establishment consensus, the lower the quality of your work and the more damaging you are to public discourse. It also contains glaring mistakes, like positioning New Republic and Slate to the left of Jacobin, and failing to distinguish meaningfully between Jacobin and Vox or The Atlantic. And again, no distinction is made between left liberalism and the socialist left, or between establishment conservatism and the alt-right.

We have to do better than this. So I tried. Here was my first crack:

I started by moving away from the left/right spectrum and instead using an equilateral triangle with three distinct poles. The chart doesn't declare any one of the three poles to be objectively "good for the discourse". But something still bothered me about it–I don't think MSNBC is closer to Jacobin's view than NYT or The Atlantic. I tried building a wall in the middle of the triangle which separates establishment sources from anti-establishment sources, to try to emphasise the difference. But as so often happens when you try to build a wall, it's not satisfying. I also couldn't think of any notable American outlets that currently occupy some kind of space between the socialist left and the alt-right which is also distinct from mainstream liberalism. My chart also looked too much like horseshoe theory:

I started by moving away from the left/right spectrum and instead using an equilateral triangle with three distinct poles. The chart doesn't declare any one of the three poles to be objectively "good for the discourse". But something still bothered me about it–I don't think MSNBC is closer to Jacobin's view than NYT or The Atlantic. I tried building a wall in the middle of the triangle which separates establishment sources from anti-establishment sources, to try to emphasise the difference. But as so often happens when you try to build a wall, it's not satisfying. I also couldn't think of any notable American outlets that currently occupy some kind of space between the socialist left and the alt-right which is also distinct from mainstream liberalism. My chart also looked too much like horseshoe theory:

The problem with these charts that involve scales or spectra is that political differences are sharper and more fundamental than this. There are different core premises underwriting these different views, and they really are separate ways of viewing the world. Any attempt to create a scale from one to another obfuscates this fact. What we really have here are three separate discussions which occur simultaneously in the media, one internally within liberalism, one internally within socialism, and one internally within the alt-right. Sometimes, people in these argue across ideological lines, but they usually don't get very far with this because either:

- They have fundamentally different core premises from their interlocutors.

- They are themselves being inconsistent and are confused about what their own view implies.

When I put Intercept and Breitbart somewhere in the middle of the two arms of my triangle, it wasn't because I really believe they occupy some coherent centrist position between the the liberal press and the more full-throated socialist or alt-right press. It's because I am not confident those publications know where they stand. They aren't sure whether they wish to retain liberal premises or discard them.

When I say "liberal premises", what do I mean? I'm talking about a set of core beliefs which underwrite most of the mainstream discourse, including both the left-liberal and establishment conservative publications. This principally includes a commitment to the idea that politics is mainly about individuals and the choices they make. Liberalism is committed on some level to individualism. This means that individuals are entitled to demand to be personally represented in some way, that their interests as an individual ought to be the thing that gets represented in democracy. This involves a conception of the person as fundamentally autonomous and exercising some form of free will.

The alt-right is different, because the alt-right thinks the world is not made up of individuals, but of primordial peoples. For the alt-right, the individual is to find meaning as part of a people, and it is the role of the state to represent its people's cultural essence. Where liberals will say that the state must find a way to accommodate difference among individuals, the alt-right will say that the state must protect and defend the culture of the national or ethnic people to whom it belongs. Liberals sometimes think about groups instead of mere individuals, but when they think about groups they don't think about them in this way. Instead of saying that each group is entitled to a state which represents it or belongs to it in some thick way, liberals propose that each group be recognised and given its due within the framework of one multicultural state. The alt-right wants nation-states, in which each "people" or "nation" gets its own state. Liberals want multinational states, in which a cosmopolitan state transcends the narrow notion of the nation and recognises the distinctive value of all individuals. The liberal person is an autonomous agent. The alt-right person is a product of a culture, an example of a people.

There is a tension there, because to this point liberals have not been able to have states without nationalism, and the alt-right has not been able to have nation-states which have not featured liberal contingents. Both liberalism and nationalism are relatively modern theories, because ancient peoples did not think primarily in terms of either individuals or national peoples. But I think we can say that these two schools of thought conceptualise the political quite differently.

The socialist left is different, because the socialist left thinks the world is not made up of individuals or of primordial peoples, but of classes. For socialists, liberal individualism leaves people alienated and atomised, denied membership in real communities by capitalism. The alt-right makes false promises of community on the basis of fictitious entities, like primordial peoples, nations, and ethnicities, while leaving the capitalist system which is responsible for the alienation and atomisation intact. Socialists want some kind of order which doesn't include it.

Unlike liberalism and nationalism, class-based frames have been around a long time and precede Karl Marx by a long way. The attention to capitalism specifically is quite modern, but you can find discussions of class conflict in Machiavelli and Aristotle. Of course, Machiavelli and Aristotle never thought this conflict could be transcended–merely managed. The idea that it is possible to get out of this and arrive at some social formation without it is more distinctively modern. Where the ancients will come up with ways of creating an order that can deal with class conflict, the modern socialists will attempt to generate this conflict in a bid to push toward the new world they envision. The socialist person is, to hearken back to Aristotle, "what they repeatedly do." For socialists, we are our jobs until we can find a way to abolish them, and in so doing become something better.

These are of course, not the only three schools of thought to have existed (the more theocratic tradition associated with divine right of kings is mostly absent from contemporary discourse, for example), and there are immense differences within each. But for a long time, virtually all of American political discourse occurred within the liberal box, and it was possible to describe American political discourse as a spectrum between left-liberals (who seek to "level the playing field" for individuals, while remaining entirely embedded in an individualist frame) and conservatives (who seek to protect the individual's property rights from the left-liberals). This is a conflict between "gentler liberal capitalism" and "more aggressive liberal capitalism". It is the conflict between Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush, or at the very most, between Lyndon Johnson and Ayn Rand.

But now this discourse is attacked, from two sides, by both a socialist discourse and an alt-right discourse, each quite distinct from liberalism and each quite distinct from the other. The socialist publications are not liberal. The liberal publications are not socialist. They both reject the alt-right. So really, it's three different boxes:

The entirety of the pre-2008 American political debate is contained within that middle box. If your chart doesn't take into account the reality that it's widened out and become more complex since then, it's not helping people. If you want a complete feel for opinion in the United States, you need to read more than the two sides of the liberal debate–you need to venture into the neighboring boxes. And if you find them too frightening, too intolerable, or too deplorable? Then you have to admit you're not going to be totally up to date on what's going on, and some major developments in our political discourse are going to happen in places you don't venture.

No comments:

Post a Comment