Sea Level Rise in Bay Area is Going to Be Much More Destructive Than We Think, Says USGS Study

The ocean is rocked by storms and its tides ebb with the moon. Waves eat away at the shore, rearranging the sand and bringing cliff-side structures crashing into the surf. It doesn't behave like water in a bathtub.

Interactive mapping tool - California inundation zones under different sea level rise scenariosBut for simplicity's sake (and because scientists are still learning about how climate change will melt glaciers), researchers have generally projected sea level rise as if the ocean will remain still and calm as it creeps up on crucial infrastructure and seaside neighborhoods.

A new study from the U.S. Geological Survey says the predicted damage from sea level rise in California triples once tides, storms and erosion are taken into account.

"There are many communities that are planning by only considering this in a bathtub and not considering the fact that that'll be on top of these episodic storm events that'll cause most of the short term impacts," said the study's lead author, Patrick Barnard, a USGS coastal geologist based in Santa Cruz.

The study showed that, once these variables are taken into account, more than $150 billion worth of property and infrastructure and about 600,000 coastal residents could be flooded by the end of the century.

Sponsored

About two-thirds of that property and those lives at risk are in and around the San Francisco Bay, said Barnard, who is the research director of the Climate Impacts and Coastal Processes Team at USGS.

"We've effectively built on an estuary with millions of people just above sea level," he said. "We're in a highly vulnerable position in the Bay Area."

More Sloshing From Storms, More Damage

When the team's mathematical models factored in the variability of the tides, beach and cliff erosion, and once-in-decades storms, the predictions for coastal communities in a warming world got grim and wet.

The locations threatened by flooding are the usual suspects: Foster City, Pacifica, and the San Francisco International Airport. Southern California will also be hit hard, with the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach inundated and whole neighborhoods in Orange County under water during big storms and high tides.

To bring it home for planners and the public, the study included an interactive onlinemapping tool with multiple layers representing different scenarios: a king tide, interventions to shore up beaches and wetlands, and various levels of sea rise. Users can look up their neighborhoods, their commutes, their favorite beaches or the port where their latest online order entered the U.S.

Most scenarios quickly put SFO under water. Others flood marinas and homes in Foster City. Highway 101 along the Peninsula gets very wet when sea level rise and storms combine.

The goal of this imagery is "to make it accessible to high-level policy people by translating the physical impacts into the socioeconomic impacts," Barnard said.

The effects of climate change are already apparent every winter, he said. For example, Highway 37 in Marin County just reopened after a levee broke during last month's storms.

"Maybe that happens once a winter every five years or something. In the future, we're going to see — instead of once or every five years —it's going to happen every year," he said.

After a couple of decades, that flooding will likely happen five times per year, then 20 times per year, Barnard said. Eventually, winter storms will send seawater creeping into areas that have never seen flooding before.

SPONSORED

Molly Peterson contributed to this report.

All of California Is Now Out of Drought, According to U.S. Drought Monitor

This particular California winter has unfolded in good news/bad news fashion. Courtesy of a string of recurring atmospheric rivers, potent storms have caused flooding, power outages and canceled flights. But they have also -- by at least one key measure -- lifted the state completely out of drought.

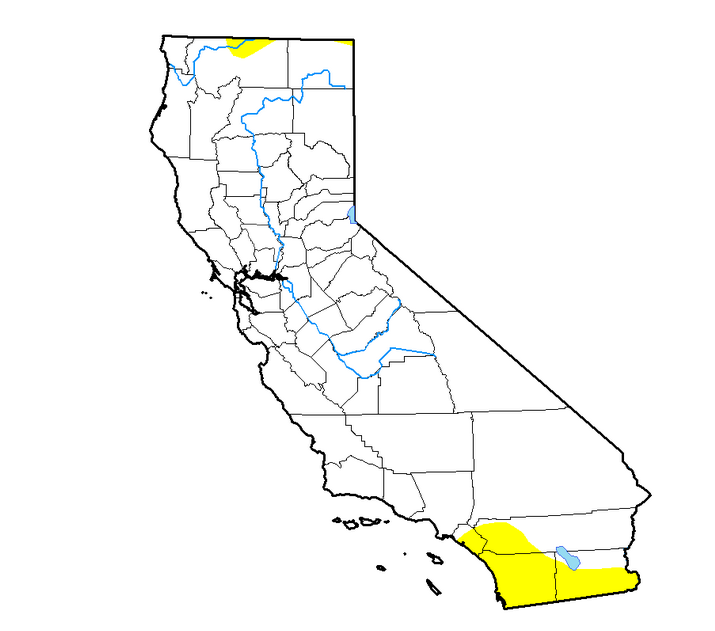

The weekly map released by the U.S. Drought Monitor on Mar. 14 shows no remaining vestiges of California in moderate-or-more severe levels of drought. Less than 7 percent of the state remains "abnormally dry" (yellow areas).

The U.S. Drought Monitor's California map shows no areas in drought, for the first time in more than seven years. (National Drought Mitigation Ctr.)

The U.S. Drought Monitor's California map shows no areas in drought, for the first time in more than seven years. (National Drought Mitigation Ctr.)It's worth noting that while the Drought Monitor, produced jointly by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is one measure of drought conditions, it's a fairly comprehensive one. Authors take a broad array of factors into account, including groundwater conditions where data is available.

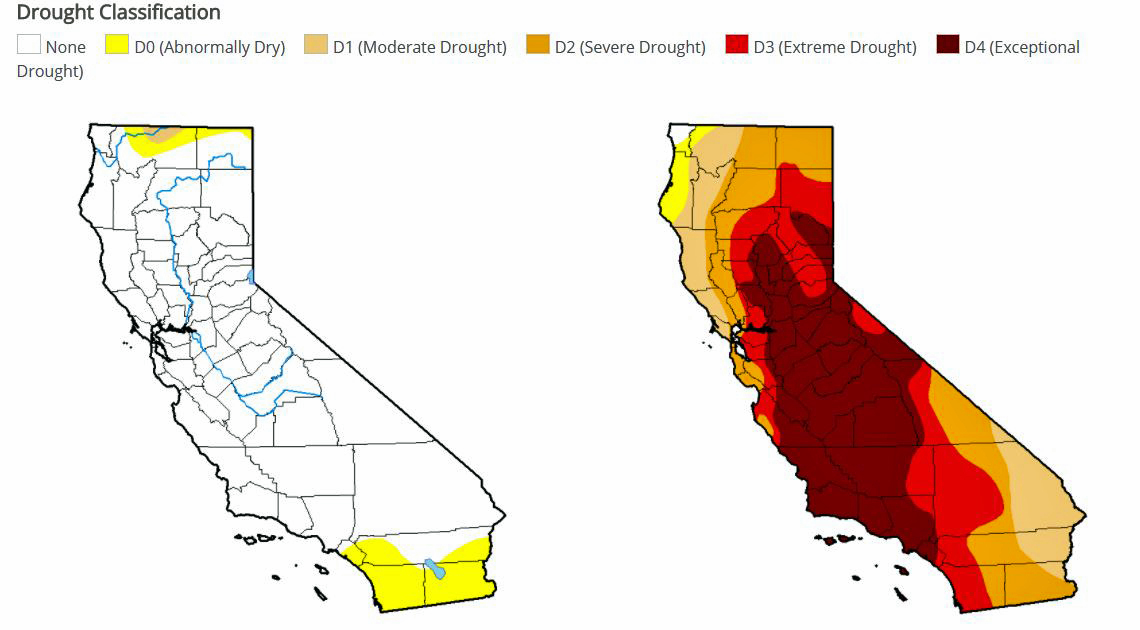

On the left, below, you can see the map released last week by the U.S. Drought Monitor, which is almost completely devoid of colors indicating various levels of parchedness. On the right is the same map from three years ago, bleeding brick-red and showing nearly 40 percent of the state in the most advanced stage of drought.

The California drought map as of March 5, 2019 is on the left. On the right is the map from March 8, 2016. (U.S. Drought Monitor)

The California drought map as of March 5, 2019 is on the left. On the right is the map from March 8, 2016. (U.S. Drought Monitor)KQED Science Managing Editor Paul Rogers recently wrote about the state's stunning water comeback for the San Jose Mercury News, where he reports on science and the environment. Here are some key points from Rogers about current water conditions in California, taken from an interview with KQED's Brian Watt (numbers reflect the Drought Monitor issued on Mar. 5.)

People were worried at one point about another drought developing. How about now?

After a dry winter last year and a dry December this year, people were starting to worry that the kind of drought conditions we saw between 2012 and 2016 might be coming back. But then it started raining like crazy, particularly in February and through early March, and those rains have really washed away fears of a returning drought. The new report showed that less than 1 percent of California, a tiny sliver up near Oregon, is still in a drought, and it's classified as "moderate." So our reservoirs are full, our rivers are full, and things are looking good in terms of the state's water supply.

Sponsored

How long has it been since the state's water tank has been this full?

You have to go back to December 2011 to find a time when such a small amount of the state has been in drought.

Just by comparison, a year ago, 47 percent of California was in drought. In March 2016, 97 percent of California was in a drought. Now we're at 1 percent.

How do the storms of this year compare to those of the past?

We have a really good historical rainfall record in San Francisco, going all the way back to 1850. In February, San Francisco saw 7.6 inches of rain. That's twice as much as the historical average and the largest amount of rain in 10 years. The month's rain total was the 16th most in a February In 169 years, according to the records.

What happened to cause the turnaround in precipitation?

Remember the "Ridiculously Resilient Ridge?" That was a big mass of high pressure air sitting in the Pacific Ocean. It acted like a large boulder in a river, blocking the storms trying to make their way to California, pushing them up into Canada and other places. That ridge is long gone, and low-pressure zones are setting up conditions where these wet atmospheric river storms from the tropics just keep barreling into the state, one after the other.

No comments:

Post a Comment