Is this any way to run a superpower?

It's not crazy to want U.S. troops to come home from Syria and Afghanistan. It is crazy for a superpower's global strategy to shift from one tweet to the next.

When I heard that Trump had tweeted the withdrawal of America's 2,000 troops from Syria, and then heard reports that he would soon pull half of our 14,000 troops out of Afghanistan, my initial reaction was: "What's wrong with that?"

I'm not a pacifist, but I judge an American intervention in a foreign war by a few simple criteria.

- Are we fighting on the right side?

- Do our soldiers have a clear mission with an achievable goal?

- Are the resources we're committing sufficient to achieve that goal?

- Do Congress and the American people believe that the goal is worth the cost, and understand the risks involved?

Weighing Syria and Afghanistan. The Syria commitment could pass that test only as long as the goal was narrowly defined: to make ISIS a stateless state again by driving it out of all its territory. Given the nature of ISIS, which is as much an idea as a caliphate, that probably won't kill it. But it should make it less of a focal point for global Muslim discontent.

What's more, the strategy laid out by President Obama was working: ISIS had lost the majority of its territory by the end of the Obama administration, and Trump more or less continued what Obama had been doing, until now ISIS has been driven back to a few small enclaves. (The claim that we had not been beating ISIS under Obama but started "winning" under Trump is the usual Trumpian bullshit.) If those enclaves were about to fall, then it was time to think about declaring victory and getting out.

The longer we stay in Syria, though, the more secondary goals the mission picks up. We're supporting rebels against the brutal Assad government that Iran and Russia back. We're protecting the Kurdish forces (who have been doing most of the fighting against ISIS) from attack by Turkey (which has its own Kurdish region and fears Kurdish nationalism).

Those might be fine things to wish for, but they don't fare well against my criteria. In particular, if we're going to be players in the Syrian civil war, we'll need a lot more than 2,000 soldiers. I don't think the American people are ready to back that kind of commitment, and I don't see how it is supposed to end.

Our Afghan commitment is harder to justify. Originally, we sent forces to Afghanistan in response to 9-11. The goal, which had close to universal support from the public at the time, was to capture or kill the people who attacked us and establish an Afghan government that wouldn't let Al Qaeda operate freely within its borders. But 17 years later, Bin Laden is long dead and our effort to stand up an effective pro-American government in Kabul has failed. It's hard to estimate a troop level that could truly pacify the country — Obama couldn't do it with 100,000 — but whatever it is, the American people aren't willing to underwrite it.

So yes, we should be trying to disengage. But here's an idea the Master of the Deal might want to consider: Couldn't we negotiate some concessions from the people who want to see our forces gone? Why just make an announcement and start pulling out?

And here's my real problem with Trump's decision: Disengagement requires a plan just as much as engagement does. Maybe I have things to do and I'm sick of standing here plugging a hole in this dike with my finger. But predictable things will happen if I pull my finger out, and how do I intend to respond when they do?

ISIS isn't defeated yet. The premise of Trump's Syria tweet was clear:

We have defeated ISIS in Syria, my only reason for being there during the Trump Presidency.

But as he so often does, Trump is claiming credit for something that hasn't happened yet. (Despite his claims, North Korea isn't denuclearized yet either, and probably won't be in the foreseeable future. And the trade deal with China he announced still hasn't been worked out.) ISIS still controls a small amount of territory, it still has fighting forces, and it has squirreled away a considerable amount of money to fund future operations.

So the job isn't done, but the US withdrawal will begin immediately. (Although Sunday's tweet described the pullout as "slow & highly coordinated".) Trump himself seemed to acknowledge this in a subsequent contradictory tweet that also happens to be false. (Russia loves that we're leaving Syria.)

Russia, Iran, Syria & many others are not happy about the U.S. leaving, despite what the Fake News says, because now they will have to fight ISIS and others, who they hate, without us.

So the first predictable thing that might happen is that ISIS stages a comeback and starts gaining territory again. What's the plan for that scenario? Accept it? Send our troops back in? Ask our Russian friends or our buddy Bashar al-Assad to handle it for us? (No, wait! Turkey will do it, according to last night's tweet. Turkish troops going deeper into Syria, which they used to rule back in the Ottoman days, where they might come into conflict with Assad, Hezbollah, and Russian forces … what could possibly go wrong? "We also discussed heavily expanded Trade.")

What's the new mission in Afghanistan? I can't find any explanation for the 7,000 figure: What is the mission of the 7,000 that will remain, and why do they no longer need the help of the 7,000 who are leaving? My intuition says that there is no new mission. "Pull out half of them" just comes from Trump's gut, and isn't based on anything.

What about the Kurds? The reason American casualties in Syria have been so low is that Kurdish militias are doing most of the actual fighting against ISIS.

The Kurds and their Syrian allies paid a severe price: They have suffered about 4,000 dead and 10,000 wounded since 2014. Over that same period, the United States lost only three soldiers in Syria, according to a U.S. military spokesperson.

Trump seems not to know these facts. "Time for someone else to fight," he tweeted, as if Americans were battling ISIS alone.

Turkey is worried about Kurdish militias operating in its own territory, which it sees as terrorism. According to AP, a December 14 phone conversation between Trump and Turkish autocrat Erdogan sparked the withdrawal decision.

Trump stunned his Cabinet, lawmakers and much of the world with the move by rejecting the advice of his top aides and agreeing to a withdrawal in a phone call with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan last week, two U.S. officials and a Turkish official briefed on the matter told The Associated Press.

The Dec. 14 call came a day after Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and his Turkish counterpart Mevlut Cavusoglu agreed to have the two presidents discuss Erdogan's threats to launch a military operation against U.S.-backed Kurdish rebels in northeast Syria, where American forces are based. The NSC then set up the call.

Pompeo, Mattis and other members of the national security team prepared a list of talking points for Trump to tell Erdogan to back off, the officials said.

But the officials said Trump, who had previously accepted such advice and convinced the Turkish leader not to attack the Kurds and put U.S. troops at risk, ignored the script. Instead, the president sided with Erdogan.

The obvious implication is that if Erdogan wants to attack the people we've been relying on to push ISIS back, he should just have at it. We'll get out of his way.

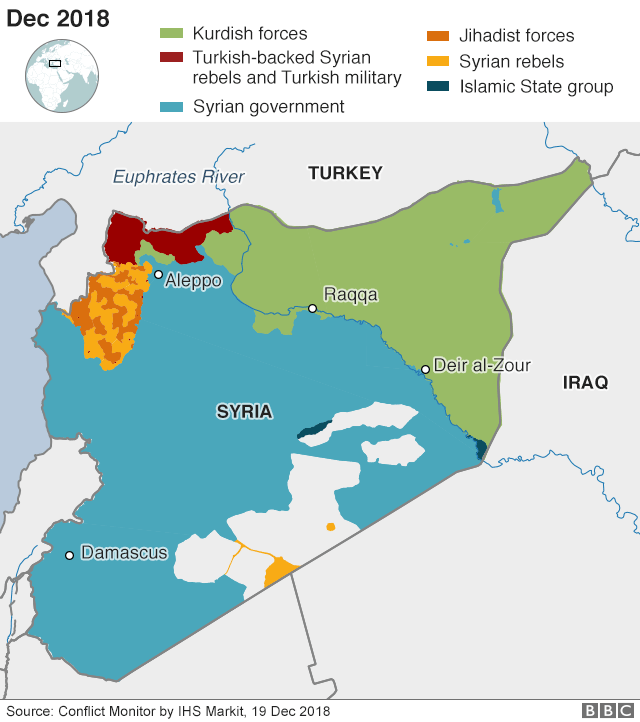

Erdogan isn't the only one likely to attack after we leave. To the Assad government, the Kurds are just one more set of rebels. What if the Kurdish region of Syria (green on the map) collapses and our former allies start getting slaughtered? What are the implications of that in other conflicts where the US wants to find local allies?

Sometimes, superpowers have to make such betrayals. We left a number of Vietnamese allies in the lurch when we exited the Vietnam War, but few Americans would want us still to be fighting there. I just wish I could believe Trump (or anyone involved in his decision process) had thought these questions out and was making these decisions strategically.

What generals and diplomats are for. There's a way that major policy changes are supposed to happen: The National Security Council meets and the various departments involved weigh in: Pentagon people talk about military implications, State Department people anticipate how our allies will react, and regional experts from the intelligence services outline the most likely scenarios. They all make their recommendations and then the President announces a decision. The advisors whose advice wasn't taken then try to talk him out of it. If the President stands firm, though, they have to yield.

Next, all the principals return to their departments with the message: This is where we're going; make plans. The plans go back to the NSC, where they get accepted or rejected. (Sometimes the President has to say one more time, "No, I really meant it. This plan doesn't do what I asked for.") Allies get consulted. Political types design a messaging strategy to explain the new policy to the American people as well as the rest of the world. Then, when all the ducks are in a row, an announcement is made and the whole government moves in unison. If things are working well, our allies move with us.

There's a reason for doing things that way: A global superpower is much bigger than the kind of family business Trump is used to running. There's more to know and more to figure out. (As an analogy, consider the different medical specialists who might get together before a particularly complicated surgery. It's not just a question of where to cut, but whether last week's infection is under control, whether the patient's heart will stand the stress, how the patient tolerates anesthesia, what kind of recovery plan is needed, and dozens of other considerations.) The various departments are in the meeting not just to protect their turf, but because they represent different kinds of expertise. You consult with the generals and diplomats because that's what they're there for. They know stuff.

Hardly any of the usual process seems to have happened in this case. The only advisor Trump seems to have listened to before making his decision is Erdogan, a foreign autocrat. (He's also the former client of Michael Flynn, for what that's worth.) The messaging strategy was for Trump to write a tweet; everybody else had to adjust on the fly.

The result is that most of the interested parties, both within our government and among our allies, were taken by surprise. As they carry out the withdrawal, no one involved can possibly have confidence that all the relevant factors were considered and all the risks foreseen.

Mattis and McGurk. Two major officials, Defense Secretary James Mattis and Special Envoy Brett McGurk, resigned in protest. Historian Michael Beschlossclaims no defense secretary has ever done this before.

Mattis' resignation letter explains his decision in terms of worldview. In Mattis' world, American power depends on its alliances, but Trump sees our allies as parasites.

One core belief I have always held is that our strength as a nation is inextricably linked to the strength of our unique and comprehensive system of alliances and partnerships…. [W]e must use all tools of American power to provide for the common defense, including providing effective leadership to our alliances.

Mattis mentions Russia and China as examples of the kind of "malign actors and strategic competitors" that we and our allies need "common defense" against, because they "want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model".

My views on treating allies with respect and also being clear-eyed about both malign actors and strategic competitors are strongly held and informed by over four decades of immersion in these issues. We must do everything possible to advance an international order that is most conducive to our security, prosperity and values, and we are strengthened in this effort by the solidarity of our alliances.

Because you have the right to have a Secretary of Defense whose views are better aligned with yours on these and other subjects, I believe it is right for me to step down from my position.

I can't help believing, though, that it's as much Trump's process as his policy that makes it impossible for Mattis to keep working with him. If a decision as important as withdrawing from a war can be made off the cuff while talking to a foreign dictator (Turkey may not be a threat as large as Russia or China, but it also a country run on an "authoritarian model".), by a President who doesn't read memos or listen to briefings, then it's not clear what role there is for people who know things.

No comments:

Post a Comment