BENJAMIN STUDEBAKER

Why Trump Cannot Bring Jobs Back With Tax Cuts

by Benjamin Studebaker

When I talk to President Trump's supporters about how they anticipate the president will bring back lost manufacturing jobs, I tend to hear the same argument over and over. It goes something like this:

- Trump will cut corporate tax and other taxes that primarily hit investors.

- Firms and investment will return from abroad to take advantage of the low tax rates.

It is possible to demonstrate that this is false. Here's how to do it.

Trump supporters tend to believe that American corporate tax rates are exceptionally high, but this is because they are looking at the nominal corporate tax rate, before tax breaks, subsidies, and other favors are taken into account. Here's the US' nominal corporate tax rate compared to the other big name industrial producers:

But of course, if corporations were simply taxed at the marginal rate, there'd be little need for paperwork or tax experts. The World Bank keeps track of taxes as a percent of commercial profits. This enables them to look at the real tax burden on firms, taking into account the legal idiosyncrasies of individual countries' tax systems, as well as the impact of taxes on labor, fuel, and property on business. When they do this, the rates change completely:

All of the sudden, the US goes from having the highest tax burden in the group to the third lowest. But what's even more interesting is that there doesn't seem to be any relation between these tax rates and a country's level of industrial output or its industrial production as a percent of GDP:

In the second to last chart, we can see:

- China, in the upper right hand corner with high manufacturing value added and a high tax percentage

- Brazil, in the lower right hand corner with low manufacturing value added and a high tax percentage

- The United States, in the upper left hand corner with high manufacturing value added and a low tax percentage

- The UK, in the lower left hand corner with a low manufacturing value added and a low tax percentage

In this last chart, we can see:

- China, in the upper right hand corner with a high manufacturing percentage and a high tax percentage

- Brazil, in the lower right hand corner with a low manufacturing percentage and a high tax percentage

- South Korea, in the upper left hand corner with a high manufacturing percentage and a low tax percentage

- The UK, in the lower left hand corner with a low manufacturing percentage and a low tax percentage

There's no clear relationship. Tax rates on business don't seem to have any decisive impact on which countries do more manufacturing, either in raw terms or as a percentage of GDP. This is largely because there are many other factors that swamp out the tax rate. Here are just a few:

- Wages–firms will tend to locate in areas where labor is cheap.

- Economic Geography–firms will tend to locate in areas where they have easy access to the natural resources and supply chains they require.

- Transportation–firms will tend to locate in areas where the cost to transport their goods to market is not prohibitive.

- Education–firms will tend to locate in areas where the local population has the relevant skills they require.

- Productivity/Automation–firms will tend to locate in areas where they can get more value per worker hired (often because they can replace large numbers of workers with cost-effective machines).

For instance, labor costs in rich countries like the US are much higher than in developing countries like China. It's not realistic for the US to cut its wages to Chinese levels, no matter what Trump does:

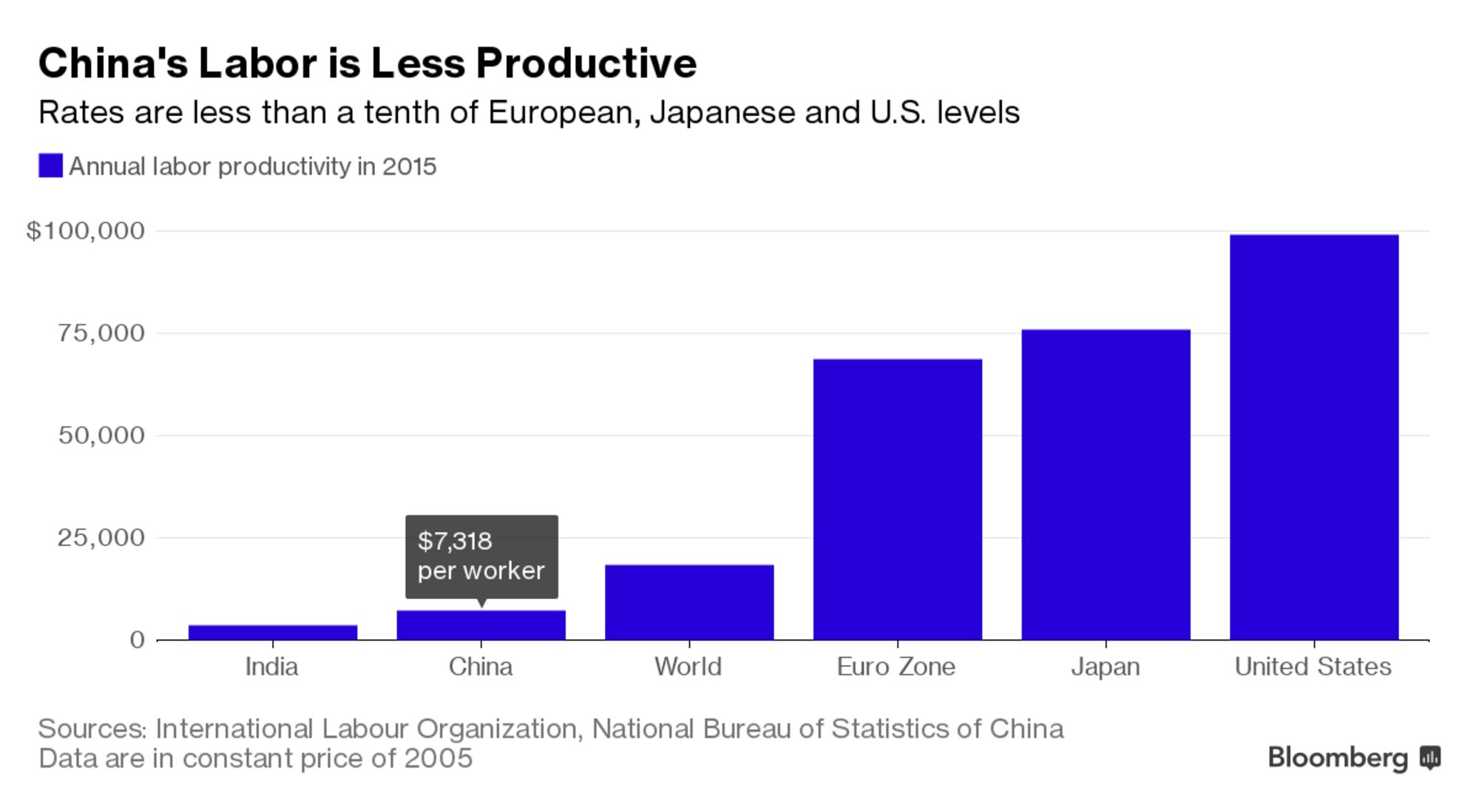

When rich countries are competitive with low-wage countries, it's often because their productivity is much higher. But the downside of high productivity is that when a firm locates itself in the United States, it typically hires far fewer workers. If you can get your desired level of output with three workers instead of thirty, why hire thirty? A firm that employed three thousand workers in the states in the 70's might return from China and employ only three hundred today. So even when firms do come back, they often doesn't bring many jobs along:

If corporate tax rates have relatively little impact on manufacturing and if those firms that do return don't supply many jobs, the primary impact of large cuts to corporate tax rates will be losses in federal revenue. If Trump cuts the corporate tax rate to 15%, it's estimated that government revenue would fall by about $240 billion per year. That's about a 10% reduction in federal revenue–more than we spend on the departments of agriculture, commerce, education, energy, interior, justice, labor, small business administration, transportation, and treasury combined plus NASA. Instead of bringing back jobs, Trump's corporate tax proposal would increase federal deficits or force reductions in federal spending–eliminating good, high-quality public sector jobs and diminishing the quality of our public services and safety nets.

Tax cuts are a blunt instrument. They're not smart.

No comments:

Post a Comment