|

Our climate change debates are out of date

Solar and batteries are going to win, and our thinking needs to adjust accordingly.

One thing that became apparent during Donald Trump's presidency was that Trump's outlook on the issues facing the nation was permanently stuck at around 1990. His paranoia over Japanese trade practices, for example, persisted long after Japanese companies no longer presented a competitive challenge. His attitudes on crime and immigration were also typical of the early 90s; by the time Trump took office, both had come way down. The world had changed, but Trump's worldview hadn't changed with it.

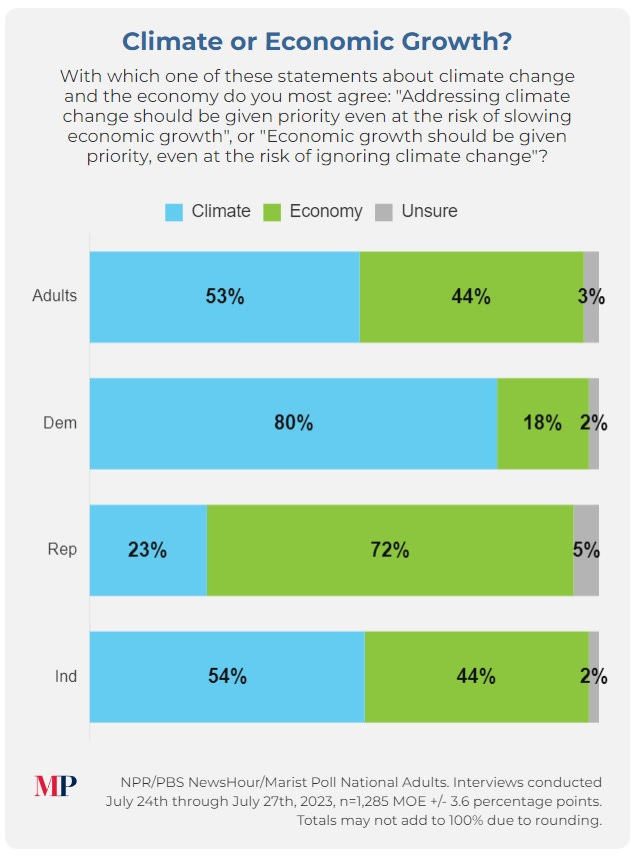

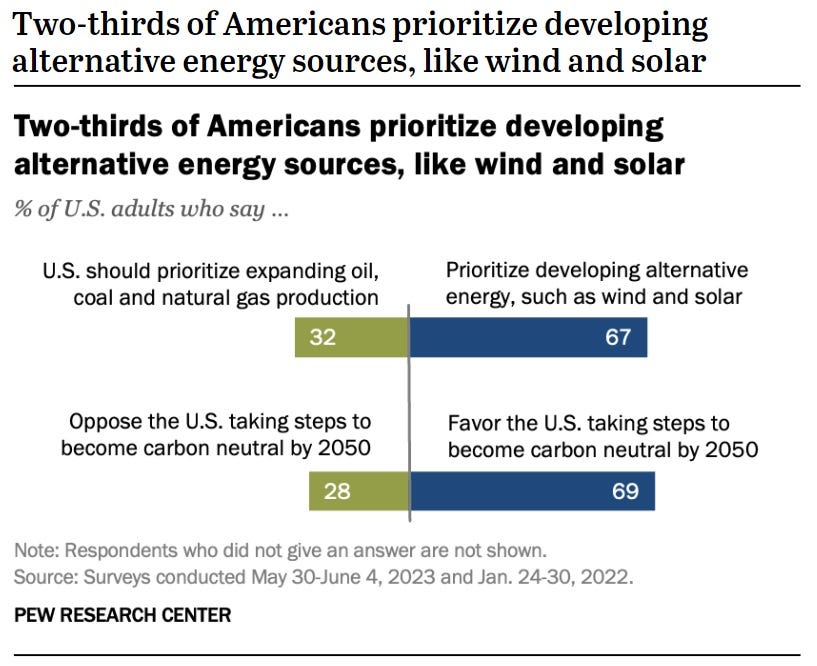

I get a little of this feeling when I watch Americans argue about climate change; the discussions seem stuck back in 2010, when solar power and electric vehicles were prohibitively expensive. For example, you still see tons of polls asking people whether they care more about economic growth or stopping climate change. For example, here's one from July 2023:

In 2010, this poll would have made sense. In 2010, decarbonizing the global economy really would have required big cutbacks in our standard of living. But to ask this question in a poll in 2023 reflects a deep misunderstanding of how technology has changed since 2010. And this misunderstanding — this failure to update our sense of what is possible — is absolutely poisoning every aspect of the climate debate in America.

A number of things have changed regarding climate change over the last 13 years. On the negative side, annual emissions continued to increase slowly or maybe plateau, leading to continued warming. This has increased the risk of wildfires, extreme heat events, and floods, and it means that the dream of holding warming below 1.5C is now basically gone. On the positive side, better climate models have all but ruled out the more extreme "apocalypse" scenarios. And more Americans believe in the reality of climate change and are concerned about its impacts.

But the most important change, by far, is the advent of cheap renewable energy, particularly solar power and batteries.

Solar and batteries are a true technological revolution

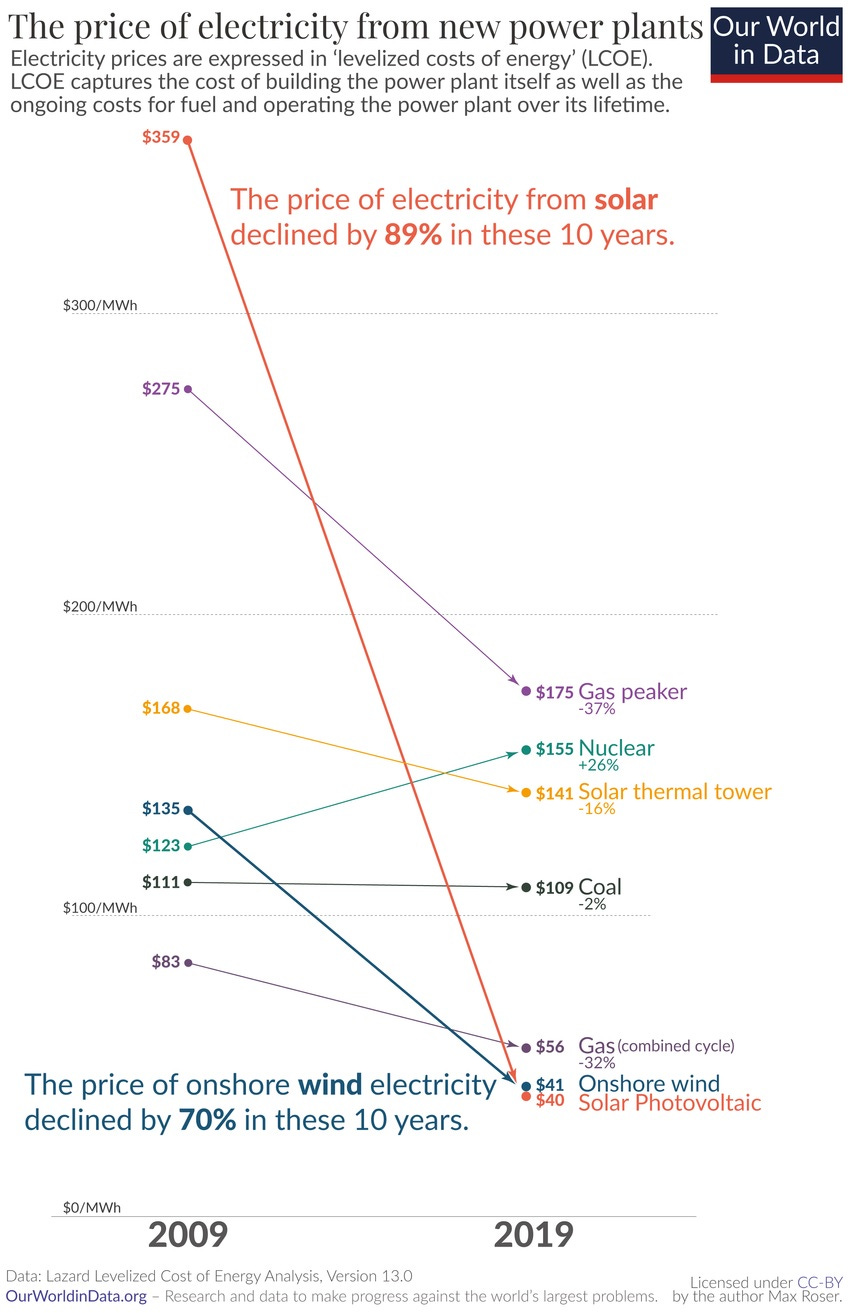

I hate to post this chart yet again, and I understand if you're annoyed, but it might be the most important chart in the world:

Costs did slightly increase over the last year, due to inflation and supply chain issues, but that bump is already reversing as inflation comes down. Cheap solar is here to stay.

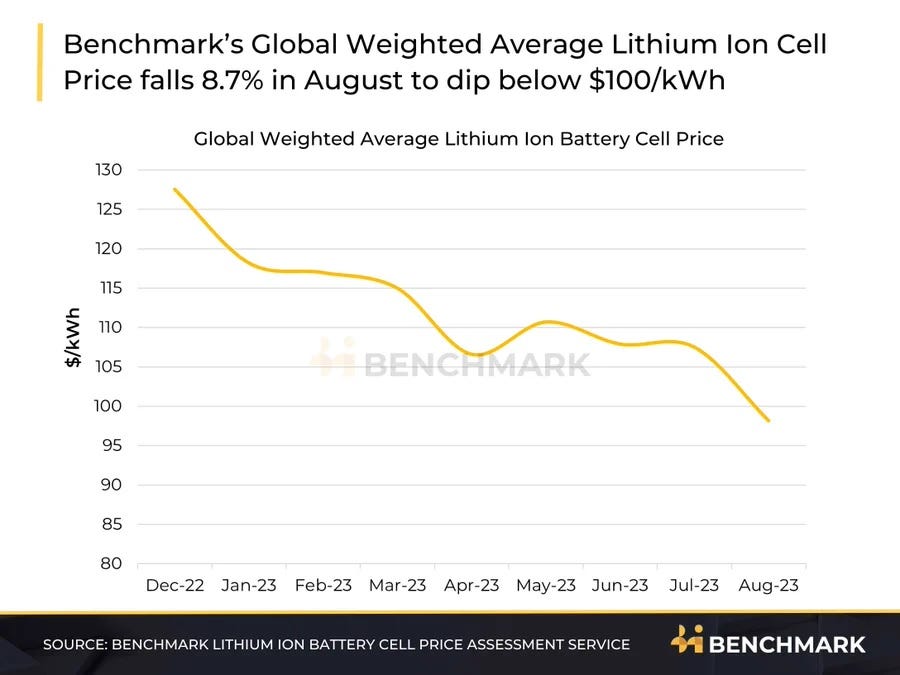

Lithium-ion batteries are on a similar trend; their costs plunged by eye-popping rates for decades, rose slightly in 2021-22, and are now declining again. Here's a recent chart:

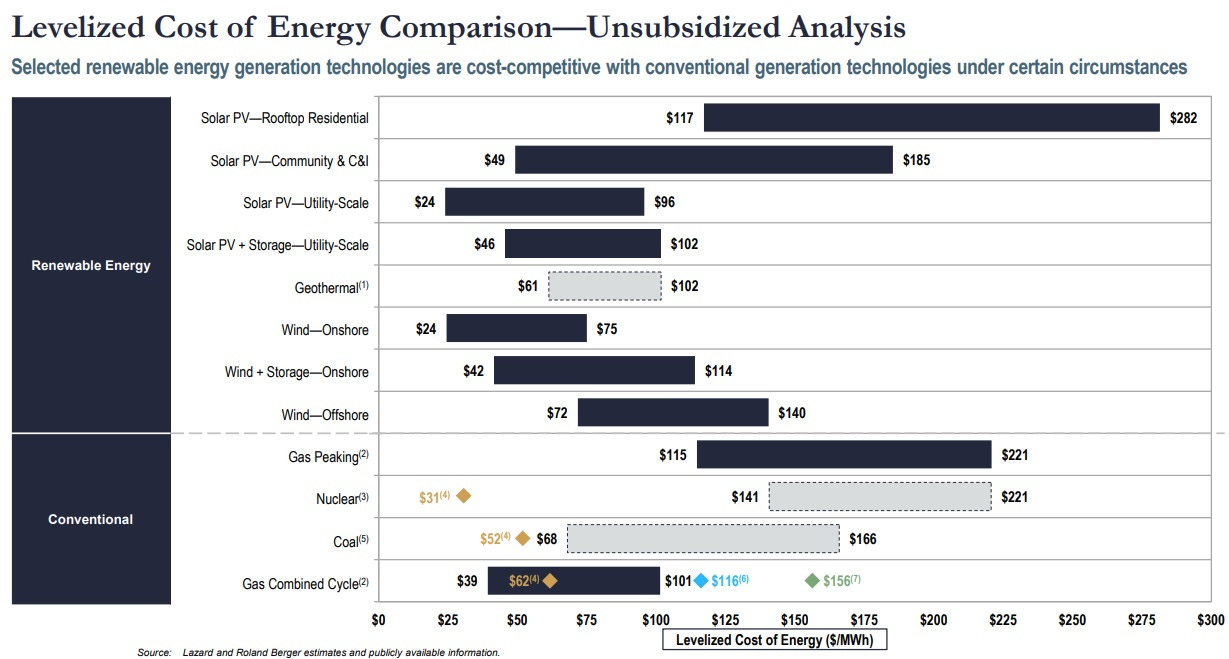

Together, cheap solar and cheap batteries mean that as of 2023, even without any subsidies, solar power is cheaper than most other ways of generating electricity — even when you factor in energy storage. Natural gas and wind are the only real competitors:

Now, levelized cost of energy isn't the only factor for power companies deciding how to produce electricity. Intermittency, reliability, and scalability all have to be taken into account.

First, let's talk about intermittency. Note that the chart above has a line for "Solar PV + Storage—Utility-Scale". Solar plus storage is not intermittent at the day-to-day frequency, and it's still pretty darn cheap, even without subsidies. Seasonality is a bigger problem; you can use batteries to store energy all year, but the amount needed is very large. The cheapest solution right now is probably just to build extra solar, but new kinds of battery chemistries are available that will make seasonal storage a lot more feasible.

Reliability is also important when you're considering how to source your electricity. Theory helps us less here, but fortunately, we have some natural experiments to draw on. Solar power with battery storage proved to be the most reliable source of power in Florida during Hurricane Ian last year:

Neighborhoods powered by solar panels with backup batteries weathered the direct onslaught of Hurricane Ian in Florida, utilities and developers said, keeping the lights on throughout the storm while millions of others lost power.

At least three solar-powered communities near Fort Myers and Tampa made it through Ian without losing electricity.

Meanwhile, Texas is increasingly relying on battery storage to harden its electrical grid against both heat waves and the occasional freak blizzard. Batteries have proven to be reliable backups when nuclear and coal plants went down. And solar is proving very reliable in heat waves.

Finally, there's the question of whether solar and batteries can scale up. If intermittency isn't a problem, the biggest challenge to scaling solar is land availability; NIMBYs try to block solar plants, just as they try to block basically any form of development, but because solar plants use a lot of land, they're more likely to run into NIMBYs than natural gas plants. For batteries, the constraint is mineral availability; though mining the minerals for batteries is far less environmentally destructive than mining fossil fuels, limited availability of lithium and we will probably have to switch to types of batteries that don't use lithium in order to get enough storage for the whole world.

These are real challenges, but I doubt they'll be prohibitive. NIMBYs are formidable in America but less so in most other countries. And if America doesn't figure out how to solve its NIMBY problem in general, our economy is in trouble from a lot more than climate change. Meanwhile, there's no reason to think that iron-air batteries or other types of batteries that rely on common minerals aren't subject to the same scaling effects as lithium-ion batteries were. So I think we'll get grid storage reasonably cheap and scalable as well.

Solar is happening right now

Now, you can choose to be a techno-pessimist about all this if you want. You can assume, if you like, that the learning curves of solar and batteries are about to hit a brick wall or go into reverse. You can assume that NIMBYs are invincible and that the lithium in lithium-ion batteries is utterly irreplaceable. You can tell yourself that other kinds of weather events (giant hail!) will be too much for solar plants to handle. You can choose to believe that humanity won't be able to build out a recycling industry to recycle massive amounts of solar panels after their 30-year lifespans. You can intone to yourself, like a protective mantra, that countries and companies and states only build solar because of politics. Yes, with enough mental effort, you can ignore a technological revolution in progress.

But ignoring a technological revolution in progress will accomplish nothing. You'll just sit in your room as the revolution goes on outside, undisturbed by your disbelief. And the solar/battery revolution is simply happening.

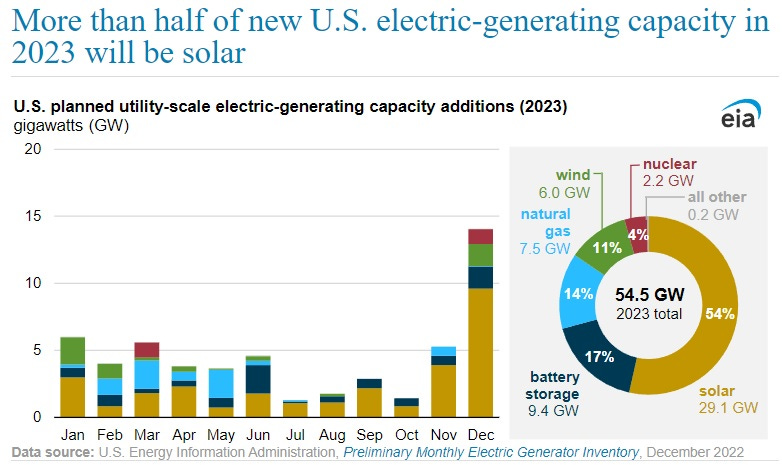

Solar and battery storage together will account for 71% of new U.S. generating capacity additions in 2023. Add other forms of green energy like wind and nuclear, and it's 86%:

Remember that capacity isn't the same as total generation, but this gives a clear idea of where things are headed — most of the new power we're building is solar and battery power.

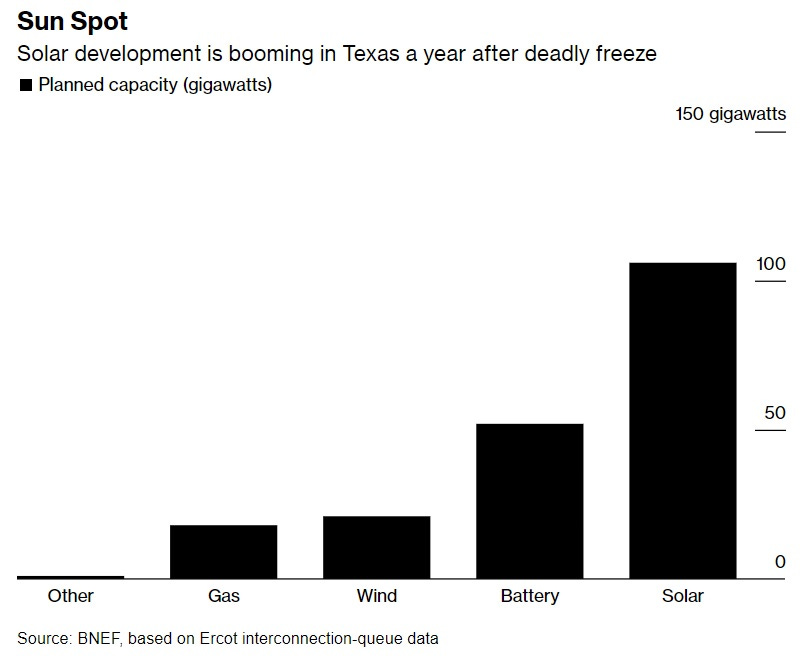

Texas, as mentioned above, is emerging as a solar-power superstar, despite the anti-solar rhetoric of some of the state's politicians:

(If politics were behind the renewables revolution, do you really think Texas would have surged ahead of California in terms of total renewable generation? I don't think so!)

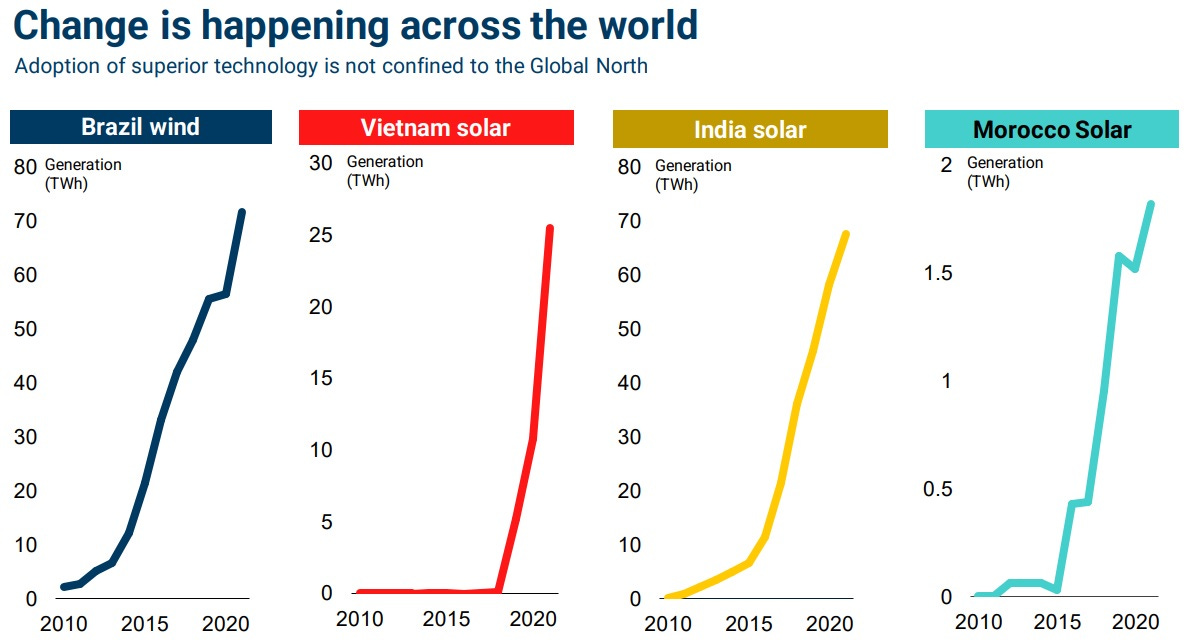

Meanwhile, beyond the U.S.' borders, the solar revolution is perhaps even more dramatic. Most EU countries are now expected to hit their 2030 solar targets years before 2030. And developing countries are racing to add solar as well:

Countries like India and Vietnam are not willing to jeopardize their economic development to placate the likes of Greta Thunberg. If they're going solar, it means it's because of one factor and one factor only: low cost.

And of course China is installing more solar than anybody.

As Stripe founder Patrick Collison pointed out, this is among the fastest deployments of a new technology in human history:

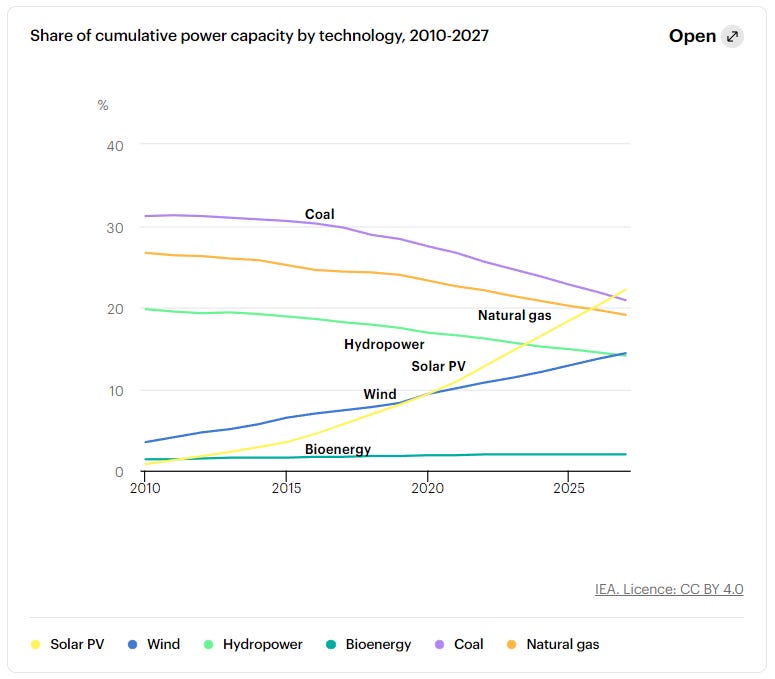

Of course, solar is still a small percentage of global energy generation — 4.5% by the IEA's latest reckoning. But a new energy source doesn't take over the entire global grid in just a couple of years. The IEA — whose predictions are famously conservative — now forecasts solar to provide a larger percent of global power capacity than either coal or natural gas in just four years:

(Of course, batteries will help transform that capacity into a similar percentage of total generation.)

In other words, you are looking at a true technological revolution in progress. It is no longer a question or a theory; it is a fact.

How the technological revolution should change our climate debates

The fact of the solar/battery revolution should change our climate debates in a number of ways.

First and foremost, it should serve as a counter to the unfortunate "doomer" trend that has taken hold in some lefty circles. Optimistic stories that highlight the positive developments I've laid out in this post, as well as other encouraging trends like falling emissions in rich countries, are starting to become more common in the media. That is good. Climate change isn't solved yet, but optimism is a strong long-term motivating force, and the solar/battery revolution gives us a fighting chance to hold the world under 2C of warming.

Climate scientists, too, ought to make sure to highlight the encouraging technological trends in their public communications. The world has already been warned very loudly about the dangers of climate change; those who still deny the threat will have to wait for heat waves and wildfires and floods to eventually convince them (and a few will go to their graves denying reality). What the world needs now is to be informed of the path out of the crisis — a path that didn't even exist back in 2010.

Next, the solar/battery revolution should make us decisively reject the idea of degrowth. Instead of forcing the human race to make sacrifices and tighten their belts, fighting climate change in the age of cheap solar and batteries will also mean creating cheap abundant energy for everyone, rich and poor alike. It will mean supercharging the development of poor countries in Africa and South Asia and elsewhere. And it'll allow people in rich countries to get even richer.

Notably, supporting renewables is Americans' preferred method of attacking climate change:

Let's give the American people what they want!

The revolution in solar and batteries should also affect the debate over electric cars. Currently, one big objection to EVs is that as long as the electrical grid is still powered by fossil fuels, EVs burn carbon indirectly. But with a solar-and-battery-powered grid, this will no longer be true.

Economists, also, should shift their policy prescriptions in response to shifts in technology. A new paper by Armitage, Bakhtian, and Jaffe shows how promoting the scaling-up of green technologies is generally more effective than carbon taxes. The instincts of the Biden administration — to use industrial policy to scale up renewables — are correct, and the inherited intuition from the debates of 2010 is out of date.

|

To sum up, climate change is one problem where new technology has completely changed the game. That doesn't mean we can sit back and rest on our laurels and let the natural progress of technology take its course — we need to act to speed up the transition even more that we're currently doing. But it means that the idea that there's a tradeoff between the economy and the climate is now defunct.

No comments:

Post a Comment