|

How did Christianity become so toxic?

Six ways conservative theology undercuts the teachings of Jesus.

If you devote much of your time to trying to make the world a better place, you've probably noticed a paradox.

On the one hand, some of your most dedicated co-workers are church people. You may not have realized it right away, because they're not the kind of Christians who say "Praise the Lord" whenever something good happens. Rather than preach at you or try to lead the group in prayer, they just show up and share the work: ladle the soup, stuff the envelopes, hammer the nails, make the phone calls. Only after you spend some down time talking do you start to understand what motivates them: They think some guy named Jesus had some pretty good ideas about healing the sick, feeding the hungry, and welcoming the stranger.

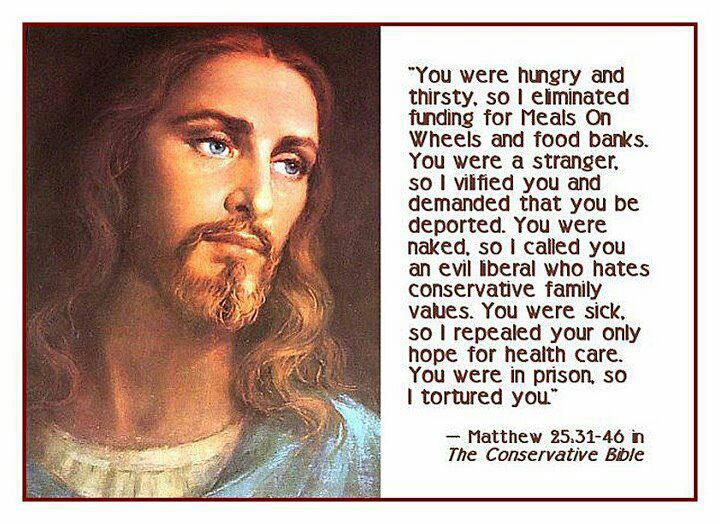

But at the same time, when you look at the bigger picture, it's hard to escape the idea that Christianity is your enemy. The loudest, best-funded, and best-organized groups working to make the world harsher, crueler, and less forgiving are the ones waving the cross. There's nothing subtle about it. All their rhetoric is about what God wants, what God hates, and the "Christian values" that the law should impose on Christians and non-Christians alike.

And strangest of all, those "Christian values" seldom have anything to do with healing the sick, feeding the hungry, or welcoming the stranger. These followers of the Prince of Peace aspire to be "spiritual warriors". They revere a man whose self-sacrifice brought forgiveness to the world, but their focus is on punishment.

The name of Jesus shows up in every paragraph of their rhetoric; his teachings, not so much.

The value of cruelty. Pretty much any time you want, you can pull examples out of the headlines. Recently, the people Christians want to punish have been kids who express the wrong gender identity or sexual orientation, as well as the adults who support them.

Until Friday, when a state judge put a stop to the practice for violating the state constitution, Texas was investigating nine families for "child abuse" because they'd been seeking medically approved treatment for their child's gender dysphoria. One child's mother commented:

I know what the law says. And yet it is terrifying to have a [Child Protective Services] worker come into your home and threaten to take your children away for doing nothing more than loving them unconditionally.

https://www.reformaustin.org/political-cartoons/refugees/

https://www.reformaustin.org/political-cartoons/refugees/Florida's new Don't Say Gay law will stop kids who are uncertain about their sexual orientation from confiding in teachers or school counselors: By law, school employees have to break their students' trust and out them to their parents; otherwise, the school district could be sued. And if you're a teacher or principal who sees elementary-school kids being bullied because of their gender expression, you can't start a conversation about that without risking a lawsuit, because such topics are not "age appropriate".

As soon as you picture either law in practice, the cruelty is obvious, and it's hard to see who benefits. But if you ask the people behind these efforts what motivates them, one answer almost always comes up: their Christian values. The Tennessee version of Don't Say Gay includes this in its list of justifications:

WHEREAS, the promotion of LGBT issues and lifestyles in public schools offends a significant portion of students, parents, and Tennessee residents with Christian values" …

Where on Earth did these "Christian values" come from? Not Jesus.

Did Jesus have "Christian values"? If you've never read the gospels, but you've listened to the people who invoke his name, you might think Jesus talked about sex and gender constantly. But in fact you'd be wrong. Homosexuality never comes up in his sermons and parables, and Jesus never rebukes his followers for getting their gender roles confused.

Sex is on the mind of the Pharisee who faults Jesus for letting a prostitute touch him, and on the minds of the men he stops from stoning an adulteress, but little in the text indicates that Jesus himself made a big deal out of people's genitals or what they did with them. (Examine, say, the parable of the sheep and the goats. None of the failings that keep people out of Heaven are sexual.)

If you believe that Jesus defines Christianity, then persecuting gay and trans people isn't a Christian value at all.

Other Christian values. Those are recent headlines, but these last few weeks have been nothing special. If I'd written this article in a different month, I might have talked about the Christians who were doing their damnedest to help a deadly virus spread freely and kill as many people as possible.

"Religious liberty" now includes churches' right to host superspreader events, which many of them have been eager to do. Rather than thank God for the scientists who found and tested a vaccine so quickly, many Christians spread lies and conspiracy theories about the vaccines ("For those of you who say you are Christians, what will your life review look like at the end of your life? Will the Lord say to you: 'You coerced people into being injected with this gene-modification technology that irreversibly disrupts your chromosomes?'"). Wearing a mask in church became evidence that you didn't trust God's protection. (But if you really trusted God, wouldn't you jump off a tall building?)

In other weeks, the headlines have been about Christian attempts to shut down discussion of systemic racism, or to stop children from learning America's racist history.

Making women bear their rapist's child is a Christian value. ("As plain as day, God spoke to me. … And I said yes Lord, I will. It's coming back. It's coming back. We are going to file that bill without any exceptions.") But miscarriage-inducing herbs have been part of women's folklore since the beginning of time. Isn't it strange that Jesus never mentioned them?

Keeping refugees and asylum-seekers out of the country is a Christian value. Some prominent pastors defended breaking up immigrant families, while others invented elaborate sophistries to explain why the Bible's many references to immigrants don't mean what they say.

The Bible warns us not to bear false witness. But Christian churches have become the prime breeding ground for the most vicious and baseless conspiracy theories.

Jesus told a young man to "sell your possessions and give to the poor". But now getting rich is a Christian value, and successful Christian preachers live in palaces and travel in personal jets.

Joel Osteen's house

Joel Osteen's house"Put away your sword," Jesus said in Gethsemane. But now gun-toting vigilantes are Christian heroes, and the faithful are carrying concealed weapons in church. (What was that about trusting God's protection?)

You know who's also a Christian hero these days? Vladimir Putin. A Republican candidate for the Senate praised Russia as a "Christian nationalist nation" and told CPAC

I identify more with Putin's Christian values than I do with Joe Biden.

As far back as 2014, Franklin Graham was lauding Putin for the even harsher Russian version of Don't Say Gay:

Isn't it sad, though, that America's own morality has fallen so far that on this issue — protecting children from any homosexual agenda or propaganda — Russia's standard is higher than our own?

And of course I have to mention the righteous politician who in 2020 garnered 80% support from White Evangelicals: a compulsive liar and conman, who has cheated on all three of his wives and traded the first two in for younger models, who can't name a single Bible verse and admits that he has never sought God's forgiveness. What a guy!

How did this happen? You might imagine that the teachings of Jesus would be a pole star for Christians, and that any time they started to drift away, the Sermon on the Mount would guide them back.

Clearly that's not happening. But why not?

The reason is simple: Jesus told stories and gave advice, but he never laid out a systematic theology or worldview. He used imagery that was designed to upend the way his disciples were thinking, but he never told them step-by-step how they should think.

So in Jesus' stories, mustard seeds — which were the scourge of Mediterranean gardeners because once mustard got into your garden you never got rid of it — were good things. An employer paid everyone the same, no matter how many hours they worked. A priest and a Levite could be bad neighbors compared to some nameless Samaritan. It was all pretty confusing.

Jesus hinted that you're not really supposed to understand right away. The Kingdom of God, he said, is like yeast; it works on you invisibly. His images and stories are supposed to sit in the back of your mind and ferment, not proceed logically from axioms to theorems.

And while that's a fine guru-to-disciple teaching technique, it leaves an opening for people who do lay out systematic theologies and worldviews, and do tell people what to think. Over the centuries that's what's happened. A conservative worldview has built up around Jesus' teachings and almost completely sealed them off.

Here's a simple example: According to John, Jesus once made this enigmatic statement: "The Father and I are one." But he never explained exactly how that worked. The result has been centuries and centuries of theological battles about the precise nature of the Trinity, arguments that have occasionally erupted into gruesome executions or even warfare.

In short: People got lost in the mystery of that one line, and wound up on the other side of the world from loving their neighbors.

How conservative theology leads people astray. Today, when you come to an Evangelical church, the main thing you are met with is a worldview that contains simple answers about what's going on in the world and how you should respond to it. Sometimes those answers are proof-texted back to something Jesus said (though more often they point back to Paul or Leviticus or some verse in Revelation that could mean just about anything). But invariably the logic only works one way: After the idea is presented to you, you can squint at one of Jesus' more puzzling statements and say "Oh, that's what he meant." But you can't walk that path in the opposite direction; what Jesus said would never lead you to the idea if some community-endorsed authority hadn't already put it in your head.

I'm not claiming this is a complete list, but here are six ways that a conservative theology and worldview tilts Evangelical thinking in directions that eventually put a wall around Jesus and his teachings.

- Focusing on the Devil opens a person to conspiracy theories.

- Believing that we're in the End Times justifies suspending normal reasoning.

- Traditional religion values tradition more than religion.

- A focus on individual souls and individual salvation makes systemic or social reasoning heretical.

- Fundamentalism promotes bad-faith reasoning.

- Christian imagery and rhetoric tilts towards autocracy.

1. The Devil is the prime conspirator. The conventional wisdom isn't always right, and occasionally powerful people do conspire for nefarious purposes. But the problem with conspiracy-theory thinking is that it's too easy: You can always come up with some way to fit current events into whatever story you want to believe. No matter what actually happens, you can make it prove that whoever you like is the hero and whoever you hate is the villain.

So if you want to live in the real world rather than some dramatic fantasy of your own choosing, you need some standards that filter out the crazy conspiracies. The most important standard is to realize that conspiring is hard. People all have their own motives and purposes, so keeping a large number of them on the same page is difficult, especially if you have to do it secretly.

So the first questions a rational person asks about a conspiracy theory are: How many people would have to commit to this, and why would they? What keeps them all pulling in the same direction? Why don't they rat each other out?

Those questions sink most conspiracy theories. Take the central Q-Anon theory for example: that the world is run by a ring of child-sex traffickers, and has been for a long time. Now picture yourself as a rising star in the world of money and politics. At what point would the conspirators reach out to you? And what if child sex wasn't your particular kink? It just seems really hard to make this work.

But now imagine you believe in the Devil. (Satan does show up in Jesus' stories, but those references are easy to misread. Our current picture of the Devil stitches together diverse Biblical characters with different names, and didn't fully congeal until a century or so after Jesus. Neil Forsyth described the process in The Old Enemy.) The Devil doesn't need a motive to launch some evil plot, because for the Devil, evil is its own reward. Minions of the Devil, likewise, do things just for the sake of being evil.

If you can imagine a core of people like that, who don't need the conspiracy to bring them wealth or power or status or any other visible benefit beyond the simple opportunity to do evil, then just about any conspiracy becomes feasible. The door to believing whatever you want is wide open.

2. Strange things happen during the End Times. In the summer of 2013, 77% of Evangelicals told the Barna Group that they agreed with this statement: "The world is currently living in the 'end times' as described by prophecies in the Bible." Evangelicals not only believe this, they seem to enjoy thinking about it: The Left Behind series of novels (based on a literalistic interpretation of the Book of Revelation) has sold more than 80 million books and inspired six movies.

Paradoxically, a belief that the world is ending soon has always been prominent in Christian circles. As far back as the first or second century AD, St. John could close his Book of Revelation with

He who testifies to these things says, "Yes, I am coming soon." Amen. Come, Lord Jesus.

That's Jesus' second coming he's talking about, the one Christians are still waiting for. Nearly two thousand years later, John's "soon" has still not turned into "now".

But in spite of this extended delay, the persistence of the end-times belief is not hard to understand. Basically, it's a form of self-aggrandizement, because it makes our lifetimes special. Nobody, apparently, wants to believe that they live in a humdrum era.

Now think about the everyday significance of that belief: More than three-quarters of conservative Christians approach the evening news the way the rest of us approach the final chapters of a novel. They expect diverse plot threads to start coming together. Connections that would ordinarily be wild coincidences are almost required. (Of course the serving girl with amnesia is the Duke's long-lost niece! I should have seen that a mile away.)

What's more, as the final battle of Good versus Evil approaches, the participants should become easier to identify. So of course there's an international conspiracy of blood-drinking child molesters. How could there not be?

3. Traditional religion is more traditional than religious. Religious teachings are one of the prime ways that a community maintains its institutions and passes down its folk wisdom. The practices in one part of the world may be completely different than those somewhere else, but you can be pretty sure that in both places, some local deity wants things to work that way.

New empires often bring new religions (which usually complete the circle by justifying the new imperial order). But community practices change much more slowly than military or political power structures. So old practices get woven into the new mythology and the new belief system, as if they had been part of the new religion all along. The annual fertility rite of a pagan deity continues, but instead is blessed by a Catholic saint. And no matter how many Islamic scholars say that the Quran does not endorse honor killings, many common people in Muslim countries keep on believing that it does.

In 21st century America, "traditional values" and "Christian values" are often used interchangeably, but they ought to be very different concepts. Countless varieties of bigotry are traditional in America: racism, sexism, antisemitism, anti-gay prejudice, and many others. Like any dominant religion, Christianity has often been co-opted to justify abusing "outsiders" (however that term has been defined at different times in different places). But custom shouldn't turn prejudices into Christian values.

4. Bias towards individuality. One of Jesus' most mysterious phrases is "the Kingdom of God". He said it a lot, and anyone who claims to know exactly what he meant by it is kidding somebody, most likely himself. Sometimes it sounds like a vision of an ideal future. Other times it seems more like a metaphor for the state of consciousness Jesus had achieved and was trying to teach. Once in a while it resembled an afterlife.

Nobody really knows. It's even possible that Jesus meant different things at different times, or that the gospels occasionally misquote him.

But in the conservative theology I was taught growing up, the Kingdom of Heaven was a literal place that I could hope to reach after death. I'd get there as an individual, because we all have individual souls, which will be judged at the end of time. There's no such thing as a collective soul (except in Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walter Wink's creative reimagining of angels).

My teachers never admitted that all this stuff about souls is speculative. It's not really spelled out anywhere in scripture. (If the sheep and goats story is supposed to be a description of literal events, it's just about the only parable that is.) Heaven is speculative also, and (like the Devil) has meant different things in different eras.

Once you've made that speculative leap, though, any kind of social thinking is going to give you problems. If good and evil are only accounted for in judgments about individuals, then good and evil must only exist in individuals.

Systemic racism, then, can only be a heresy. If racism is evil, then that evil has to be accountable to individuals, not to systems. If stealing is a sin, then the man who steals a loaf of bread is guilty, and not the society that left him no other way to feed his family. If enslaving people is evil, then George Washington, Robert E. Lee, and many other people we might want to admire were evil. Slavery can't be blamed on society, because society will never stand before St. Peter and be sent to Heaven or Hell. So maybe slavery wasn't really so bad.

Theologians created these problems by going too far out on a limb. They've constructed a semi-logical structure around some hints in scripture, and that structure leads them into absurdities and injustices.

5. From apologetics to bad-faith denial. Apologetics is the art of using rational argument to support positions that originate in faith. It often looks like philosophy, but it isn't, because practitioners aren't reasoning in order to find truth. Instead, they believe they've already found truth through their faith, and are now just trying to persuade others. So apologists start with their conclusions already established, and try to tie them to convincing first principles via logic.

Apologetics can be an honorable practice if the apologists are open about what they're doing. (And philosophy can even benefit if the arguments are sharp enough. Aquinas' Summa Theologicae proudly claims to be apologetic, but philosophers still read it.) The practice goes back at least as far as the Middle Ages, and is still taught in seminaries.

But for most of its history, apologetics was an esoteric field of study. Parishioners in the pews might believe what they were taught or doubt it, but they didn't really care whether St. Anselm's proof of the existence of God was sound.

That all changed in the 19th century, when geologists discovered a world far older than Genesis described, and biologists developed a theory of human origins very different from God shaping Adam out of dust. Science was now invading turf that had previously belonged to religion, and many religious people believed they had to fight back.

That was the origin of fundamentalism.

But a problem soon became apparent: If you restrict yourself facts and logic, Genesis is just wrong. If you're going to argue that it's right (without invoking faith), you have to cheat. You have to make bad-faith scientific arguments and hope you can sell them. So fundamentalists did that. They're still doing it.

The result was that fundamentalist churches encouraged their members to reason badly, and to accept any kind of nonsense if it supported a literal interpretation of the Bible. In essence, they built a back door into their members' reasoning processes. But in the long run, that kind of corner-cutting always has unforeseen consequences. In the subsequent decades, self-induced gullibility has made fundamentalists prey to intellectual hackers and conmen of all sorts.

Today, motivated reasoning is the rule in Evangelical churches, and has spread to topics that have little to do with the Bible. So Evangelical churches have become centers of climate change denial and Covid denial, as well as hotbeds of Q-Anon conspiracy thinking. Rose-colored views of American history — where the Founders are latter-day prophets, slavery wasn't really so bad, and the Native American genocide shouldn't be examined too closely — are practically dogma among White Evangelicals.

Evolution denial established the notion that if enough people don't want to believe some true thing, it's OK for them to support each other in denying it. That genie is out of its bottle now, and it will work ever-greater mischief in conservative churches until they recognize the problem they have made for themselves.

The Divine Monarchy. When monotheism replaced polytheism, the Universe began to be viewed as a vast autocratic system. You can see the transition happening already in Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, written in the fifth century BC. There are still many gods at this point, but the sky god is sovereign to the point of tyranny. In the opening scene, the personification of Power explains to Hephaistos why he must complete the disagreeable job of chaining Prometheus to the mountain: "Zeus alone is free."

Jesus often talked about the Kingdom of Heaven, but St. Paul supported worldly kings in Romans 13:

Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. Consequently, whoever rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves.

If we know that Heaven is a kingdom, then maybe Earth should be a kingdom too. Maybe we should find the godliest man we can (of course it has to be a man), and do whatever he says. (And by the way, have I told you about the lying, womanizing, unrepentant, Bible-illiterate conman all the other Christians are voting for? Maybe he's the guy.)

Today, Christians talk about "Christ the King" and say "Jesus is Lord!" with the enthusiasm of football fans saying "We're #1!" But again, Jesus never laid out his political theory. If you think you know what kind of theocracy Jesus wants you to establish, or even who Jesus thinks you should vote for, you're standing at the end of a long chain of speculation.

I can't tell you what Jesus would think, but I can tell you what I think: If that long chain of speculation has you supporting cruelty, and if it gets in the way of healing the sick, feeding the hungry, and welcoming the stranger, then you probably did it wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment