Reset: Investigations Post Mueller

Bob Mueller testified to two congressional committees Wednesday, the Judiciary Committee in the morning and the Intelligence Committee in the afternoon. [full transcript] For weeks it has felt as if everything related to impeachment and investigation has been on hold, waiting for Mueller's testimony. Now Mueller is done: He finished his investigation, wrote his report, and testified about it in public. Mueller time is over; those of us who want Trump to be investigated and/or impeached won't get any more help from him.

So let's think about where we are and what we know. There are two sides to the investigation: the Russia side and the Trump side.

What Russia did. The Russia side of the picture is becoming fairly clear: The Putin government was trying to get Trump elected, and it succeeded.

Russian operatives hacked the DNC and Clinton campaign chair John Podesta, and then used WikiLeaks to orchestrate the release of the stolen emails at a pace and in a manner designed to keep Clinton constantly on defense. In parallel, Russia ran a sophisticated disinformation operation on social media with two main purposes: suppressing the black vote and preventing Bernie Sanders' supporters from reconciling with Clinton. (Coincidentally, those were also goals of the Trump campaign.)

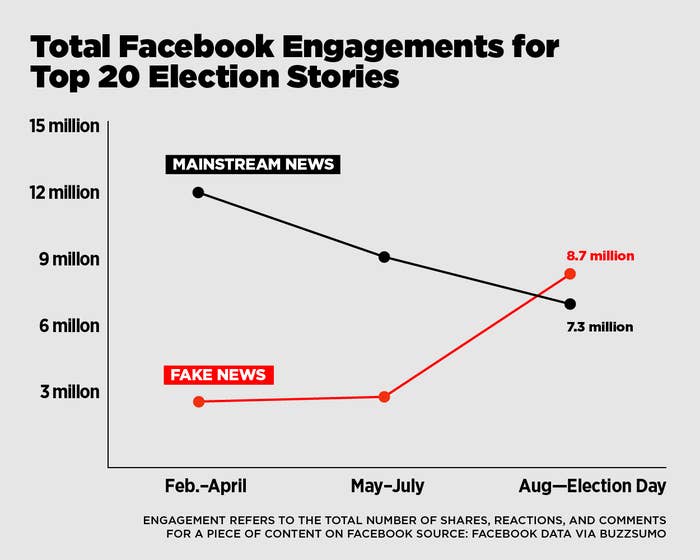

This was far more than the "couple of Facebook ads" in Jared Kushner's disparaging claim. For example, the Russians created the fake "Blacktivist" identity, which had half a million Facebook followers. At one point the fake @TEN_GOP Twitter account had ten times more Twitter followers than the actual Tennessee Republican Party. Altogether there were more than 470 such groups. They helped propagate fake news stories like "WikiLeaks confirms Hillary sold weapons to ISIS" and "FBI Agent Suspected in Hillary Email Leaks Found Dead in Apparent Murder-Suicide". (The Russians weren't responsible for the entire fake-news ecosystem, but they helped.) The impact of fake news [1] on the election was huge.

There is still no evidence that they actively reached into voting machines and changed vote totals, but that's not for lack of trying. Reportedly, Russia tried to penetrate election systems in all 50 states. According to the Senate Intelligence Committee, "Russian cyberactors were in a position to delete or change voter data" in the Illinois voter database. Whether they used that capability or not, the possibility has big implications for the future: If Russia wanted to, say, suppress the Hispanic vote in Florida, why not just delete the registrations of some or all voters with Hispanic names? They wouldn't have to be inside the voting machines to swing an election.

Did the Russian activities make a difference? Yeah, probably. Without them, it's likely Trump would not be president.

What Trump's people did. From the beginning of the Trump/Russia investigation, I've had two questions about the Trump campaign and Trump transition team:

- Why did Trump's people have so many interactions with Russian officials, Russian oligarchs, and other people connected to Vladimir Putin?

- When they were asked about those interactions, why did they all lie?

Those two questions have formed my standard of judgment ever since: If I ever felt like I could confidently answer them, I would believe we had gotten to the bottom of things.

I don't think we have good answers to those questions even now.

I can imagine a relatively innocent answer for the first one: The Russians were trying to infiltrate the campaign, so they repeatedly contacted Trump's people. But that answer just makes the second question more difficult, because then Trump's people could have given perfectly innocent answers, like: "I wondered about that at the time. It seemed so weird that these Russians kept wanting to talk to me." It would have been so easy to say: "Yeah, I talked to the guy, but I never figured out exactly what he wanted. I had a bad feeling about it, though, so I didn't see him again." Instead, they either made false denials, manufactured false cover stories, or developed a convenient amnesia around all things Russian.

Why? Innocent people don't act that way.

Trump and his defenders have not offered an answer of any kind about the lying, and instead have done everything possible to distract us the question. All the wild conspiracy theories about the Steele dossier, the "angry Democrats" in Mueller's office, Mueller's supposed "conflicts", the "witch hunt", and so forth — it all has nothing to do with the two basic questions: Why meet with so many Russians? Why lie about it?

We still don't know.

Obstruction of justice. One reason we don't know more about those questions is that President Trump obstructed the investigation. This is pretty clear if you read the Mueller report: Volume 2 examines ten instances that might be obstruction, and finds all three elements of the definition of obstruction in seven of them. [2]

Two of the seven instances stand out: telling White House Counsel Don McGahn to fire Mueller, and witness-tampering with Paul Manafort. The first stands out because it is the clearest: McGahn refused because he knew at the time he was being asked to obstruct justice. (Trump apparently knew also; why else would he order McGahn to lie about it later?)

The second stands out because it might have had the biggest impact: Manafort was Trump's campaign chairman, and was also feeding campaign information to a Russian intelligence operative. Honest testimony from Manafort might have told us exactly what Russia wanted to know, and maybe even what it did with that information. At one point, Manafort agreed to cooperate with Mueller's investigation, but ultimately he lied to investigators and may have spied on Mueller for Trump.

If Manafort did that out of love, that's one thing. But if he did it expecting that Trump will pardon him before leaving office, that's witness tampering. Whyever he did it, Manafort closed the door on our best chance to know what really happened. [3]

Mueller's report and testimony. Attorney General Barr did an amazing job of obfuscating Mueller's written report: He delayed releasing the redacted version for several weeks, and in the meantime left us with the impression that the investigation had found nothing significant. Trump started summarizing Mueller's conclusion as "No collusion, no obstruction" — which was false, but not provably false until later. "No collusion" was just a lie, and "no obstruction" was the conclusion Barr had been hired to announce; it was not Mueller's conclusion.

Mueller's actual conclusion about obstruction is subtle and easy to exaggerate in either direction. Department of Justice guidelines would not have allowed him to indict Trump while in office. Given that guidance, he concluded that it would be irresponsible to write a report saying that Trump obstructed justice, since there would be no trial in which Trump could dispute that claim. If, on the other hand, the facts allowed him to dismiss the obstruction claims, reporting that would be within his mandate.

Mueller was unable to dismiss the claims of obstruction, but he intentionally avoided making a charging decision. I read him as saying that someone who does have charging ability — either Congress now or a U.S. attorney after Trump leaves office — should look at the evidence he has assembled and make a charging decision. [4]

So it's possible to quote Mueller and imply either that he is asserting or denying that Trump obstructed justice. Neither is quite true.

Media response. That kind of nuance doesn't play well on TV, and so Mueller's testimony this week didn't produce the pivotal moment Democrats were looking for. He was asked to directly contradict several Trump talking points and did. (He testified that his investigation was not a witch hunt, Russian interference was not a hoax, his report did not exonerate Trump, etc. He also agreed that Trump's written testimony was "generally" incomplete and untruthful.) But he did not tell the Judiciary Committee to start impeachment proceedings, or explain clearly to the American public why they should.

In addition to Mueller's lawyerly reticence to exceed his role or speculate beyond what he could prove, he also appeared to have aged since the last time he had testified to Congress. He seemed tired and at times confused. He chose not to fight with Republican congressmen who put forward a variety of conspiracy theories that no one outside the Fox News bubble has heard of.

In short, he is not the man to rally the nation against its corrupt ruler.

For the most part, pundits judged Mueller's testimony like a reality TV show. Jennifer Rubin critiqued the response:

I worry that we — the media, voters, Congress — are dangerously unserious when it comes to preservation of our democracy. To spend hours of airtime and write hundreds of print and online reports pontificating about the "optics" of Mueller's performance — when he confirmed that President Trump accepted help from a hostile foreign power and lied about it, that he lied when he claimed exoneration, that he was not completely truthful in written answers, that he could be prosecuted after leaving office and that he misled Americans by calling the investigation a hoax — tells me that we have become untrustworthy guardians of democracy.

The "failure" is not of a prosecutor who found the facts but might be ill equipped to make the political case, but instead, of a country that won't read his report and a media obsessed with scoring contests rather than focusing on the damning facts at issue.

What now? The burden now rests in two places: on House Democrats and on the general public.

The Judiciary Committee is continuing to seek information, and the Trump administration is continuing to stonewall it. In a court filing Friday, the Committee asked to receive evidence collected by Mueller's grand jury. The filing implies that the Committee is already conducting a preliminary impeachment investigation.

the House must have access to all the relevant facts [regarding the president's conduct] and consider whether to exercise its full Article I powers, including a constitutional power of the utmost gravity—approvals of articles of impeachment.

Unfortunately, the mills are grinding very slowly. The Committee still has not filed suit to enforce its subpoena of Dan McGahn, for example. That case might take months to wind its way up to the Supreme Court, and then we'll see just how partisan this Court is: In numerous cases (like the Muslim ban) it has refused to look into possible illicit hidden motives of the executive branch. The case to block this subpoena is based on claims about the illicit hidden motives of the legislative branch. Will the Supremes rule that they are empowered to second-guess a Democratic Congress in ways that they can't second-guess Republican president? That would be a striking message that the rule of law is essentially dead.

The other way this progresses is if the people rise up and demand impeachment, the way that people have risen up in Puerto Rico or Hong Kong. But will we?

[1] This is "fake news" in the original sense: posts designed to resemble news sites, but based on pure flights of fantasy. Trump later stole the term and now uses it to refer to any report he doesn't like. But it once had an important meaning.

One striking feature of the Mueller report is how often a story that Trump labeled "fake news" was actually true.

[2] In addition, Trump refused to testify in person, and his lawyers threatened a subpoena fight that would have delayed the investigation for months or maybe years. Mueller eventually submitted a small number of tightly constrained questions, which Trump (or his lawyers) answered in writing. Nearly all his answers were some version of "I don't remember." Trump's testimony, then, was neither incriminating nor exculpatory, because there was no real information in it.

[3] This is the difference between Trump's "no collusion" mantra, and what Mueller really reported: that he could not assemble sufficient evidence to charge anyone in the Trump campaign with criminal conspiracy. Rather than "No collusion, no obstruction", the real story might be "insufficient evidence of conspiracy, because obstruction succeeded".

[4] About 700 former federal prosecutors have read Mueller's report and said that they would charge Trump with obstruction, based on the evidence Mueller cites.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18280574/wheel2.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18282919/929097246.jpg.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18280584/mustard2.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18282891/587969380.jpg.jpg)