The skyline of Manhattan at sunset in New York, May 23, 2018.

Photo: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

THIS SUNDAY, THE entire New York Times Magazine will be composed of just one article on a single subject: the failure to confront the global climate crisis in the 1980s, a time when the science was settled and the politics seemed to align. Written by Nathaniel Rich, this work of history is filled with insider revelations about roads not taken that, on several occasions, made me swear out loud. And lest there be any doubt that the implications of these decisions will be etched in geologic time, Rich's words are punctuated with full-page aerial photographs by George Steinmetz that wrenchingly document the rapid unraveling of planetary systems, from the rushing water where Greenland ice used to be to massive algae blooms in China's third largest lake.

The novella-length piece represents the kind of media commitment that the climate crisis has long deserved but almost never received. We have all heard the various excuses for why the small matter of despoiling our only home just doesn't cut it as an urgent news story: "Climate change is too far off in the future"; "It's inappropriate to talk about politics when people are losing their lives to hurricanes and fires"; "Journalists follow the news, they don't make it — and politicians aren't talking about climate change"; and of course: "Every time we try, it's a ratings killer."

None of the excuses can mask the dereliction of duty. It has always been possible for major media outlets to decide, all on their own, that planetary destabilization is a huge news story, very likely the most consequential of our time. They always had the capacity to harness the skills of their reporters and photographers to connect abstract science to lived extreme weather events. And if they did so consistently, it would lessen the need for journalists to get ahead of politics because the more informed the public is about both the threat and the tangible solutions, the more they push their elected representatives to take bold action.

The Aug. 5, 2018, issue of the New York Times Magazine.

Image: Courtesy of the New York Times

That's also why it is so enraging that the piece is spectacularly wrong in its central thesis.

According to Rich, between the years of 1979 and 1989, the basic science of climate change was understood and accepted, the partisan divide over the issue had yet to cleave, the fossil fuel companies hadn't started their misinformation campaign in earnest, and there was a great deal of global political momentum toward a bold and binding international emissions-reduction agreement. Writing of the key period at the end of the 1980s, Rich says, "The conditions for success could not have been more favorable."

And yet we blew it — "we" being humans, who apparently are just too shortsighted to safeguard our future. Just in case we missed the point of who and what is to blame for the fact that we are now "losing earth," Rich's answer is presented in a full-page callout: "All the facts were known, and nothing stood in our way. Nothing, that is, except ourselves."

Yep, you and me. Not, according to Rich, the fossil fuel companies who sat in on every major policy meeting described in the piece. (Imagine tobacco executives being repeatedly invited by the U.S. government to come up with policies to ban smoking. When those meetings failed to yield anything substantive, would we conclude that the reason is that humans just want to die? Might we perhaps determine instead that the political system is corrupt and busted?)

This misreading has been pointed out by many climate scientists and historians since the online version of the piece dropped on Wednesday. Others have remarked on the maddening invocations of "human nature" and the use of the royal "we" to describe a screamingly homogenous group of U.S. power players. Throughout Rich's accounting, we hear nothing from those political leaders in the Global South who were demanding binding action in this key period and after, somehow able to care about future generations despite being human. The voices of women, meanwhile, are almost as rare in Rich's text as sightings of the endangered ivory-billed woodpecker — and when we ladies do appear, it is mainly as long-suffering wives of tragically heroic men.

All of these flaws have been well covered, so I won't rehash them here. My focus is the central premise of the piece: that the end of the 1980s presented conditions that "could not have been more favorable" to bold climate action. On the contrary, one could scarcely imagine a more inopportune moment in human evolution for our species to come face to face with the hard truth that the conveniences of modern consumer capitalism were steadily eroding the habitability of the planet. Why? Because the late '80s was the absolute zenith of the neoliberal crusade, a moment of peak ideological ascendency for the economic and social project that deliberately set out to vilify collective action in the name of liberating "free markets" in every aspect of life. Yet Rich makes no mention of this parallel upheaval in economic and political thought.

In this May 9, 1989 file photo, James Hansen, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, testifies before a Senate transportation subcommittee on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., a year after his history-making testimony telling the world that global warming was here and would get worse.

Photo: Dennis Cook/AP

WHEN I DELVED into this same climate change history some years ago, I concluded, as Rich does, that the key juncture when world momentum was building toward a tough, science-based global agreement was 1988. That was when James Hansen, then director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, testified before Congress that he had "99 percent confidence" in "a real warming trend" linked to human activity. Later that same month, hundreds of scientists and policymakers held the historic World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere in Toronto, where the first emission reduction targets were discussed. By the end of that same year, in November 1988, the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the premier scientific body advising governments on the climate threat, held its first session.

But climate change wasn't just a concern for politicians and wonks — it was watercooler stuff, so much so that when the editors of Time magazine announced their 1988 "Man of the Year," they went for "Planet of the Year: Endangered Earth." The cover featured an image of the globe held together with twine, the sun setting ominously in the background. "No single individual, no event, no movement captured imaginations or dominated headlines more," journalist Thomas Sancton explained, "than the clump of rock and soil and water and air that is our common home."

(Interestingly, unlike Rich, Sancton didn't blame "human nature" for the planetary mugging. He went deeper, tracing it to the misuse of the Judeo-Christian concept of "dominion" over nature and the fact that it supplanted the pre-Christian idea that "the earth was seen as a mother, a fertile giver of life. Nature — the soil, forest, sea — was endowed with divinity, and mortals were subordinate to it.")

When I surveyed the climate news from this period, it really did seem like a profound shift was within grasp — and then, tragically, it all slipped away, with the U.S. walking out of international negotiations and the rest of the world settling for nonbinding agreements that relied on dodgy "market mechanisms" like carbon trading and offsets. So it really is worth asking, as Rich does: What the hell happened? What interrupted the urgency and determination that was emanating from all these elite establishments simultaneously by the end of the '80s?

Rich concludes, while offering no social or scientific evidence, that something called "human nature" kicked in and messed everything up. "Human beings," he writes, "whether in global organizations, democracies, industries, political parties or as individuals, are incapable of sacrificing present convenience to forestall a penalty imposed on future generations." It seems we are wired to "obsess over the present, worry about the medium term and cast the long term out of our minds, as we might spit out a poison."

When I looked at the same period, I came to a very different conclusion: that what at first seemed like our best shot at lifesaving climate action had in retrospect suffered from an epic case of historical bad timing. Because what becomes clear when you look back at this juncture is that just as governments were getting together to get serious about reining in the fossil fuel sector, the global neoliberal revolution went supernova, and that project of economic and social reengineering clashed with the imperatives of both climate science and corporate regulation at every turn.

The failure to make even a passing reference to this other global trend that was unfolding in the late '80s represents an unfathomably large blind spot in Rich's piece. After all, the primary benefit of returning to a period in the not-too-distant past as a journalist is that you are able to see trends and patterns that were not yet visible to people living through those tumultuous events in real time. The climate community in 1988, for instance, had no way of knowing that they were on the cusp of the convulsive neoliberal revolution that would remake every major economy on the planet.

But we know. And one thing that becomes very clear when you look back on the late '80s is that, far from offering "conditions for success [that] could not have been more favorable," 1988-89 was the worst possible momentfor humanity to decide that it was going to get serious about putting planetary health ahead of profits.

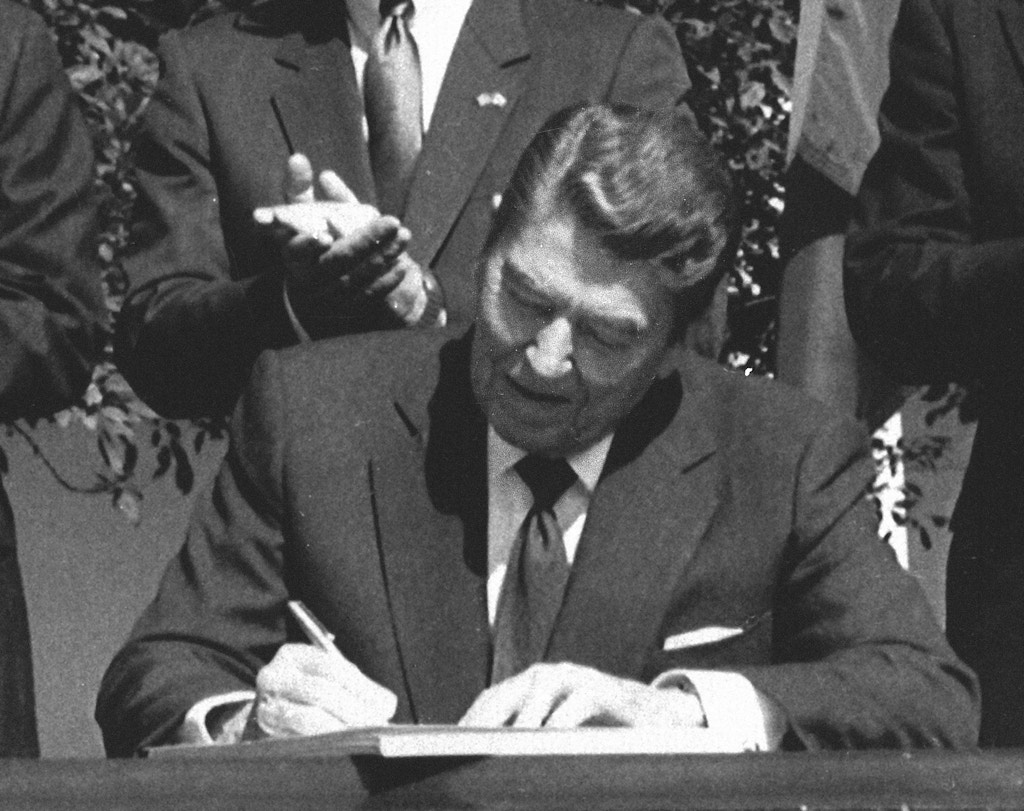

President Ronald Reagan signs legislation implementing the U.S.-Canada free trade agreement during a ceremony at the White House, Sept. 28, 1988.

Photo: Scott Stewart/AP

RECALL WHAT ELSE was going on. In 1988, Canada and the U.S. signed their free trade agreement, a prototype for NAFTA and countless deals that would follow. The Berlin wall was about to fall, an event that would be successfully seized upon by right-wing ideologues in the U.S. as proof of "the end of history" and taken as license to export the Reagan-Thatcher recipe of privatization, deregulation, and austerity to every corner of the globe.

It was this convergence of historical trends — the emergence of a global architecture that was supposed to tackle climate change and the emergence of a much more powerful global architecture to liberate capital from all constraints — that derailed the momentum Rich rightly identifies. Because, as he notes repeatedly, meeting the challenge of climate change would have required imposing stiff regulations on polluters while investing in the public sphere to transform how we power our lives, live in cities, and move ourselves around.

All of this was possible in the '80s and '90s (it still is today) — but it would have demanded a head-on battle with the project of neoliberalism, which at that very time was waging war on the very idea of the public sphere ("There is no such thing as society," Thatcher told us). Meanwhile, the free trade deals being signed in this period were busily making many sensible climate initiatives — like subsidizing and offering preferential treatment to local green industry and refusing many polluting projects like fracking and oil pipelines — illegal under international trade law.

I wrote a 500-page book about this collision between capitalism and the planet, and I won't rehash the details here. This extract, however, goes into the subject in some depth, and I'll quote a short passage here:

We have not done the things that are necessary to lower emissions because those things fundamentally conflict with deregulated capitalism, the reigning ideology for the entire period we have been struggling to find a way out of this crisis. We are stuck because the actions that would give us the best chance of averting catastrophe — and would benefit the vast majority — are extremely threatening to an elite minority that has a stranglehold over our economy, our political process, and most of our major media outlets. That problem might not have been insurmountable had it presented itself at another point in our history. But it is our great collective misfortune that the scientific community made its decisive diagnosis of the climate threat at the precise moment when those elites were enjoying more unfettered political, cultural, and intellectual power than at any point since the 1920s. Indeed, governments and scientists began talking seriously about radical cuts to greenhouse gas emissions in 1988 — the exact year that marked the dawning of what came to be called "globalisation."

Why does it matter that Rich makes no mention of this clash and instead, claims our fate has been sealed by "human nature"? It matters because if the force that interrupted the momentum toward action is "ourselves," then the fatalistic headline on the cover of New York Times Magazine – "Losing Earth" — really is merited. If an inability to sacrifice in the short term for a shot at health and safety in the future is baked into our collective DNA, then we have no hope of turning things around in time to avert truly catastrophic warming.

If, on the other hand, we humans really were on the brink of saving ourselves in the '80s, but were swamped by a tide of elite, free-market fanaticism — one that was opposed by millions of people around the world — then there is something quite concrete we can do about it. We can confront that economic order and try to replace it with something that is rooted in both human and planetary security, one that does not place the quest for growth and profit at all costs at its center.

And the good news — and, yes, there is some — is that today, unlike in 1989, a young and growing movement of green democratic socialists is advancing in the United States with precisely that vision. And that represents more than just an electoral alternative — it's our one and only planetary lifeline.

Yet we have to be clear that the lifeline we need is not something that has been tried before, at least not at anything like the scale required. When the Times tweeted out its teaser for Rich's article about "humankind's inability to address the climate change catastrophe," the excellent eco-justice wing of the Democratic Socialists of America quickly offered this correction: "*CAPITALISM* If they were serious about investigating what's gone so wrong, this would be about 'capitalism's inability to address the climate change catastrophe.' Beyond capitalism, *humankind* is fully capable of organizing societies to thrive within ecological limits."

Their point is a good one, if incomplete. There is nothing essential about humans living under capitalism; we humans are capable of organizing ourselves into all kinds of different social orders, including societies with much longer time horizons and far more respect for natural life-support systems. Indeed, humans have lived that way for the vast majority of our history and many Indigenous cultures keep earth-centered cosmologies alive to this day. Capitalism is a tiny blip in the collective story of our species.

But simply blaming capitalism isn't enough. It is absolutely true that the drive for endless growth and profits stands squarely opposed to the imperative for a rapid transition off fossil fuels. It is absolutely true that the global unleashing of the unbound form of capitalism known as neoliberalism in the '80s and '90s has been the single greatest contributor to a disastrous global emission spike in recent decades, as well as the single greatest obstacle to science-based climate action ever since governments began meeting to talk (and talk and talk) about lowering emissions. And it remains the biggest obstacle today, even in countries that market themselves as climate leaders, like Canada and France.

But we have to be honest that autocratic industrial socialism has also been a disaster for the environment, as evidenced most dramatically by the fact that carbon emissions briefly plummeted when the economies of the former Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s. And as I wrote in "This Changes Everything," Venezuela's petro-populism has continued this toxic tradition into the present day, with disastrous results.

Let's acknowledge this fact, while also pointing out that countries with a strong democratic socialist tradition — like Denmark, Sweden, and Uruguay — have some of the most visionary environmental policies in the world. From this we can conclude that socialism isn't necessarily ecological, but that a new form of democratic eco-socialism, with the humility to learn from Indigenous teachings about the duties to future generations and the interconnection of all of life, appears to be humanity's best shot at collective survival.

These are the stakes in the surge of movement-grounded political candidates who are advancing a democratic eco-socialist vision, connecting the dots between the economic depredations caused by decades of neoliberal ascendency and the ravaged state of our natural world. Partly inspired by Bernie Sanders's presidential run, candidates in a variety of races — like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York, Kaniela Ing in Hawaii, and many more — are running on platforms calling for a "Green New Deal" that meets everyone's basic material needs, offers real solutions to racial and gender inequities, while catalyzing a rapid transition to 100 percent renewable energy. Many, like New York gubernatorial candidate Cynthia Nixon and New York attorney general candidate Zephyr Teachout, have pledged not to take money from fossil fuel companies and are promising instead to prosecute them.

These candidates, whether or not they identify as democratic socialist, are rejecting the neoliberal centrism of the establishment Democratic Party, with its tepid "market-based solutions" to the ecological crisis, as well as Donald Trump's all-out war on nature. And they are also presenting a concrete alternative to the undemocratic extractivist socialists of both the past and present. Perhaps most importantly, this new generation of leaders isn't interested in scapegoating "humanity" for the greed and corruption of a tiny elite. It seeks instead to help humanity — particularly its most systematically unheard and uncounted members — to find their collective voice and power so they can stand up to that elite.

We aren't losing earth — but the earth is getting so hot so fast that it is on a trajectory to lose a great many of us. In the nick of time, a new political path to safety is presenting itself. This is no moment to bemoan our lost decades. It's the moment to get the hell on that path.

No comments:

Post a Comment