If you've used the internet at any point in the past few weeks, you've probably heard of Juicero. Juicero is a San Francisco-based company that sells a $400 juicer. Here's how it works: you plug in a pre-sold packet of diced fruits and vegetables, and the machine transforms it into juice. But it turns out you don't actually need the machine to make the juice. On 19 April, Bloomberg Newsreported that you can squeeze the packets by hand and get the same result. It's even faster.

The internet erupted in laughter. Juicero made the perfect punchline: a celebrated startup that had received a fawning profile from the New York Times and $120m in funding from blue-chip VCs such as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Google Ventures was selling an expensive way to automate something you could do faster for free. It was, in any meaningful sense of the word, a scam. And it tickled social media's insatiable schadenfreude for rich people getting swindled – not unlike the spectacle of wealthy millennials fleeing the cheese sandwiches and feral dogs of the Fyre festival.

Juicero is hilarious. But it also reflects a deeply unfunny truth about Silicon Valley, and our economy more broadly. Juicero is not, as its apologists at Vox claim, an anomaly in an otherwise innovative investment climate. On the contrary: it's yet another example of how profoundly anti-innovation America has become. And the consequences couldn't be more serious: the economy that produced Juicero is the same one that's creating opioid addicts in Ohio, maimingauto workers in Alabama, and evicting families in Los Angeles.

These phenomena might seem worlds apart, but they're intimately connected. Innovation drives economic growth. It boosts productivity, making it possible to create more wealth with less labor. When economies don't innovate, the result is stagnation, inequality, and the whole horizon of hopelessness that has come to define the lives of most working people today. Juicero isn't just an entertaining bit of Silicon Valley stupidity. It's the sign of a country committing economic suicide.

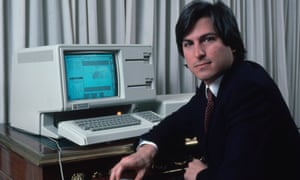

At the root of the problem is the story we tell ourselves about innovation. Stop me if you've heard this one before: a lone genius disappears into a garage, preferably in Palo Alto, and emerges with an invention that changes the world. The engine of technological progress is the entrepreneur – the fast-moving, risk-loving, rule-breaking visionary in the mold of Steve Jobs.

This story has been so widely repeated as to become a cliche. It's also inaccurate. Contrary to popular belief, entrepreneurs typically make terrible innovators. Left to its own devices, the private sector is far more likely to impede technological progress than to advance it. That's because real innovation is very expensive to produce: it involves pouring extravagant sums of money into research projects that may fail, or at the very least may never yield a commercially viable product. In other words, it requires a lot of risk – something that, myth-making aside, capitalist firms have little appetite for.

This creates a problem. Companies need breakthroughs to build businesses on, but they generally can't – or won't – fund the development of those breakthroughs themselves. So where does the money come from? The government. As the economist Mariana Mazzucato has shown, nearly every major innovation since the second world war has required a big push from the public sector, for an obvious reason: the public sector can afford to take risks that the private sector can't.

Conventional wisdom says that market forces foster innovation. In fact, it's the government's insulation from market forces that has historically made it such a successful innovator. It doesn't have to compete, and it's not at the mercy of investors demanding a share of its profits. It's also far more generous with the fruits of its scientific labor: no private company would ever be so foolish as to constantly give away innovations it has generated at enormous expense for free, but this is exactly what the government does. The dynamic should be familiar from the financial crisis: the taxpayer absorbs the risk, and the investor reaps the reward.

From energy to pharma, from the shale gas boom to lucrative lifesaving drugs, public research has everywhere laid the foundation for private profit. And the industry that produced Juicero has been an especially big beneficiary of government largesse. The advances that created what we've come to call tech – the development of digital computing, the invention of the internet, the formation of Silicon Valley itself – were the result of sustained and substantial government investment. Even the iPhone, that celebrated emblem of capitalist creativity, wouldn't exist without buckets of government cash. Its core technologies, from the touch-screen display to GPS to Siri, all trace their roots to publicly funded research.

More recently, however, austerity has gutted the government's capacity to innovate. As a share of the economy, funding for research has been falling for decades. Now it's being cut to its lowest level as a percent of GDP in forty years. And Republicans want to see it fall even further: the budget blueprint that Trump released in March promisesdeep reductions in science funding.

Decades of tax cuts have also undermined innovative potential. Ironically, these cuts were sold as measures to stimulate innovation, by unleashing the dynamism of the private sector. The biggest drop in the capital gains tax came in the late 1970s, when the National Venture Capital Association successfully lobbied Congress to slash the rate in half by claiming that VCs had created the internet. This is how we got a tax code under which Warren Buffett pays a lower tax rate than his secretary.

VCs didn't create the internet, of course – and they haven't funded much innovation with the additional wealth they acquired from pretending they did. In fact, VCs are anti-innovation by design. They want a big payday for their partners on a short timetable, typically looking for start-ups headed for an exit – an IPO or an acquisition by a bigger company – within three to five years. This isn't a recipe for nurturing actual breakthroughs, which require more patient financing over a longer timeframe. But it's a good formula for producing nonsense like the Juicero, or overvalued companies that serve as lucrative vehicles for financial speculation.

What about corporations? If VCs aren't filling the void created by the collapse of public research, neither are big companies. Few of them put significant resourcesinto basic research any more. It's not like they don't have the money – monopoly profits and tax evasion have enabled Apple to amass a cash pile of a quarter of a trillion dollars. But the conquest of corporate America by the financial sector ensures that cash won't be put to productive purposes. Wall Street is more interested in extracting wealth than creating it. It would rather companies cannibalize themselves by shoveling out profits to their shareholders in the form of stock buybacks and dividends than let them invest in their capacity for growth.

As the public sector starves, the private sector grows ever more bloated and predatory. The economy becomes a mechanism for making the rich richer, and the money that might be used to finance the next internet is allocated to sports cars and superyachts. The result isn't just fewer miraculous inventions, but substantially weaker growth. Since the 1970s, the American economy has grown far more slowly than during its mid-century golden age – and wages have flatlined. Wealth has been redistributed upwards, where it piles up wastefully while the mass of the people who created it continue their downward slide.

It's hard to imagine a more irrational way to organize society. Capitalism prides itself on allocating resources well – if it creates inequality, its defenders argue, at least it also creates growth. Increasingly, that's no longer the case. In its infinite wisdom, capitalism is eating itself alive. A saner system would recognize that innovation is too precious to leave to the private sector and that capitalism, like all utopian projects, works better in theory than in practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment