Why Democrats Should Ignore the Chatter About Moving 'Too Far Left' and Go Big

Backlash is inevitable. So Democrats should be bold.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey hold a news conference for their proposed Green New Deal at the Capitol in February 2019. (Reuters / Jonathan Ernst)

Ready To Fight Back?

Sign up for Take Action Now and get three actions in your inbox every week.You will receive occasional promotional offers for programs that support The Nation's journalism. You can read our Privacy Policy here.

The 2018 midterms brought an infusion of fresh blood, new ideas, and youthful energy into the Democratic caucus on Capitol Hill, and a number of lawmakers—notably those with presidential aspirations—are pushing ambitious, unapologetically progressive proposals to solve some very serious problems. The most prominent may be Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's Green New Deal, but there several others: Senator Bernie Sanders's proposal to significantly expand the inheritance tax; Senator Elizabeth Warren's wealth tax and universal-childcare plan; Senator Kirsten Gillibrand's bid to put predatory lenders out of business by empowering the Post Office to serve as a community bank; Senator Cory Booker's proposal to use "baby bonds" to close the racial wealth gap and, of course, various versions of Medicare for All. And in the House, Democrats are championing a comprehensive proposal to advance key voting rights and curb the influence of deep-pocketed donors.

While it's an exciting moment for progressives who have long urged Democrats to embrace these kinds of bold policy ideas, it's also unleashed a predictable flood of hand-wringing from pundits, conservatives, and more moderate Democrats about whether the Dems are moving "too far to the left." Rather than acknowledging that their own policy preferences hew to the center or the right, the story they tell is that Dems risk alienating college-educated suburban women or disenchanted Trump voters or some other group they ostensibly need to win over in 2020. We also hear endless concerns over the "price tag" for these kinds of policies—never mind that such questions don't seem to come up when we're talking about defense spending or high-end tax-cuts.

It's a safe bet that these kinds of worries will be a staple of mainstream editorial pages and cable news panels for the foreseeable future. But we should really ignore them. Here's why.

The first reason may seem depressing on its face, but could ultimately be liberating. There's good evidence suggesting that voters punish the two major parties for enacting their agendas, and it doesn't seem to matter that much what those agendas are. In other words, in this highly polarized environment, electoral backlash is inevitable, regardless of whether or not a party is seen as moderate or tries to "find common ground" with its political opponents. Negative partisanship is a powerful force.

RELATED ARTICLE

The fight over the Affordable Care Act illustrates this perfectly. The ACA wasn't, in fact, a scheme first championed by the conservative Heritage Foundation, but it did feature the same basic approach. In an effort to make the bill bipartisan, Barack Obama launched "endless efforts to cajole and encourage and beg and plead for Republican support," as Paul Waldman wrotein The American Prospect in 2012, none which kept the GOP from calling it a "government takeover" of the health-care system that would leave millions of families in ruins and literally kill your grandmother.

In other words, Democrats can try to prevent backlash by compromising with the GOP, but they will probably find that it's coming either way. Matt Grossman, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan State University, looked at the electoral consequences of major legislation dating back to the early 1950s, and he made a compelling case that the kind of resistance Obamacare faced could have been anticipated. According to his research, when Democrats have passed significant laws, it's consistently energized their opposition, and the same is true for Republicans: As we saw in November, when they enact their agenda, fired-up Dems come out and punish them at the polls.

In an article for FiveThirtyEight titled, "Voters Like A Political Party Until It Passes Laws," Grossman wrote that while "it might not sound intuitive,…policy victories usually result in a mobilized opposition and electoral losses [as] voters usually punish rather than reward parties that move policy to achieve their goals." It's a dynamic that results from a two-party system in which "neither party seems capable of sustaining a public majority to carry out its governing vision to completion" because their congressional majorities are "simply too narrow and short-lived."

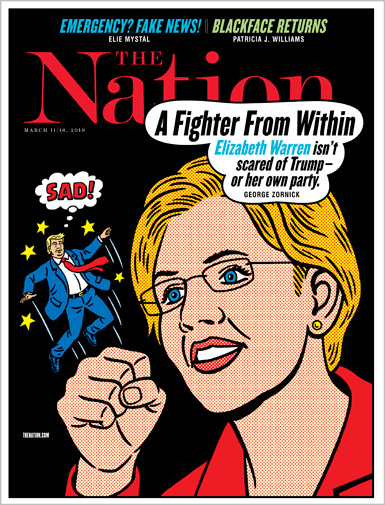

CURRENT ISSUE

Subscribe today and Save up to $129.

When Republicans are in power, they tend to pursue a maximalist conservative agenda, even when public opinion isn't with them. Last year's tax scam was a good example. Many of us on the left attribute the GOP's tendency to overreach to the fact that they know shifting demographics are not on their side, and they're trying to lock in as many structural advantages as possible while they can. But perhaps they simply understand that electoral backlash is inevitable in a way that Democrats haven't fully embraced.

If a backlash is inevitable, you might as well go big. But here's an important caveat: Not all backlashes are created equal. Some dissipate relatively quickly. The Republican uprising over the Affordable Care Act came and went; the law became much more popular just a few years later when Republicans attacked it. That wasn't the case with the backlash against California Republicans after then-Governor Pete Wilson ran a notably xenophobic campaign in 1994 and then pushed a series of measures that would bar undocumented immigrants from public education and health services. The party hasn't recovered yet in the Golden State.

And there are also areas where pursuing a given policy is worth any painful electoral consequences that may follow. Climate change represents a policy area where we face something of a choice between taking sweeping and uncompromising action or facing potential catastrophe. As Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said after conservatives panned her arguably over-ambitious proposal to tackle the climate crisis, "We simply don't have any other choice. If it's radical to propose a solution on the scale of the problem, so be it."

The other reason to ignore the hand-wringing over the Dems' increasingly progressive agenda is that several studies have found that voters don't punish presidential candidates, at least, for taking positions that the pundits view as "extreme." Summarizing the data inThe Washington Post, George Washington University political scientist John Sides wrote that the data show "there is scarcely any penalty for being extreme. To put it bluntly: Candidates may be extreme because they can get away with it." (He added that while conventional wisdom holds that Barry Goldwater and George McGovern lost badly in 1964 and 1972, respectively, because they were outside the mainstream, "this had as much if not more to do with the fundamental conditions in the country, not with their own ideological positions.")

SUPPORT PROGRESSIVE JOURNALISM

If you like this article, please give today to help fund The Nation's work.

Sides cautions that one shouldn't conclude that "candidate policy views have no impact whatsoever," but "it does mean that an American public that is not that ideological may not use ideology as a shortcut in voting for presidential candidates. And this in turn allows presidential candidates to have views well to the left or right of the average voter."

Political scientists Christopher Achens and Larry Bartels have argued convincingly that most voters just don't have a solid grasp of public policy and take their cues from politicians they admire and other influential voices. So there is a danger that the media's relentless drumbeat about these proposals supposedly being outside the mainstream could convince voters that the criticism has merit.

That's why we shouldn't just ignore all the hand-wringing about Dems' going too far. We need to push back against it aggressively before it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez speaks during a rally in front of the White House, February 12, 2019, in Washington, D.C. Over the weekend, Ocasio-Cortez tweeted that her office was going to ensure a living wage for all her staffers.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez speaks during a rally in front of the White House, February 12, 2019, in Washington, D.C. Over the weekend, Ocasio-Cortez tweeted that her office was going to ensure a living wage for all her staffers.